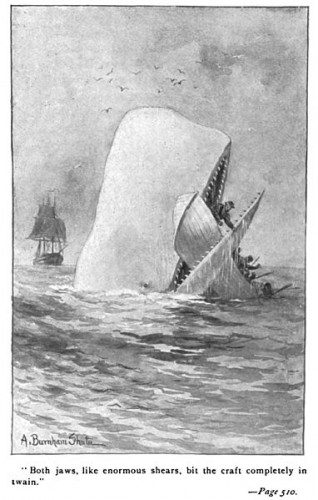

The True-Life Horror that Inspired Moby-Dick [via David Angsten}

|

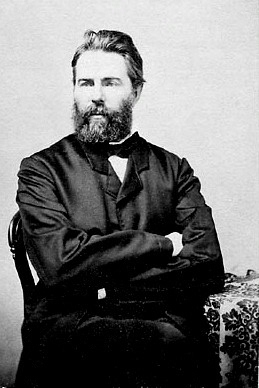

Herman Melville, circa 1860.

|

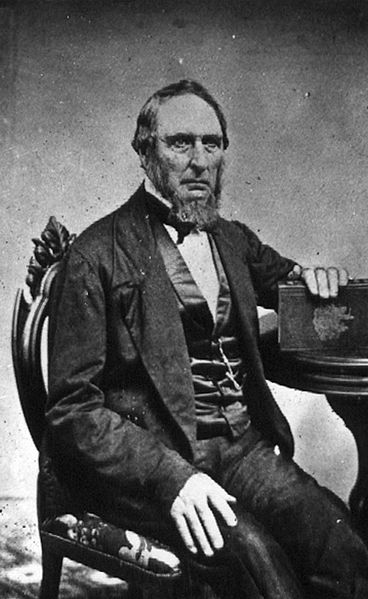

And on his last day on Nantucket he met the broken-down 60-year-old man who had captained the Essex, the ship that had been attacked and sunk by a sperm whale in an 1820 incident that had inspired Melville’s novel. Captain George Pollard Jr. was just 29 years old when the Essex went down, and he survived and returned to Nantucket to captain a second whaling ship, Two Brothers. But when that ship wrecked on a coral reef two years later, the captain was marked as unlucky at sea—a “Jonah”—and no owner would trust a ship to him again. Pollard lived out his remaining years on land, as the village night watchman.

Pollard had told the full story to fellow captains over a dinner shortly after his rescue from the Essex ordeal, and to a missionary named George Bennet. To Bennet, the tale was like a confession. Certainly, it was grim: 92 days and sleepless nights at sea in a leaking boat with no food, his surviving crew going mad beneath the unforgiving sun, eventual cannibalism and the harrowing fate of two teenage boys, including Pollard’s first cousin, Owen Coffin. “But I can tell you no more—my head is on fire at the recollection,” Pollard told the missionary. “I hardly know what I say.”

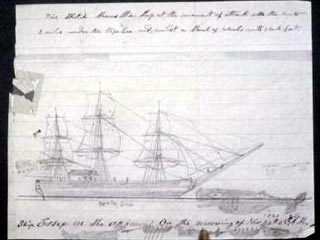

The trouble for Essex began, as Melville knew, on August 14, 1819, just two days after it left Nantucket on a whaling voyage that was supposed to last two and a half years. The 87-foot-long ship was hit by a squall that destroyed its topgallant sail and nearly sank it. Still, Pollard continued, making it to Cape Horn five weeks later. But the 20-man crew found the waters off South America nearly fished out, so they decided to sail for distant whaling grounds in the South Pacific, far from any shores.

To restock, the Essex anchored at Charles Island in the Galapagos, where the crew collected sixty 100-pound tortoises. As a prank, one of the crew set a fire, which, in the dry season, quickly spread. Pollard’s men barely escaped, having to run through flames, and a day after they set sail, they could still see smoke from the burning island. Pollard was furious, and swore vengeance on whoever set the fire. Many years later Charles Island was still a blackened wasteland, and the fire was believed to have caused the extinction of both the Floreana Tortoise and the Floreana Mockingbird.

| ||

| Essex First Mate Owen Chase, later in life. |

By November of 1820, after months of a prosperous voyage and a thousand miles from the nearest land, whaleboats from the Essex had harpooned whales that dragged them out toward the horizon in what the crew called “Nantucket sleigh rides.” Owen Chase, the 23-year-old first mate, had stayed aboard the Essex to make repairs while Pollard went whaling. It was Chase who spotted a very big whale—85 feet in length, he estimated—lying quietly in the distance, its head facing the ship. Then, after two or three spouts, the giant made straight for the Essex, “coming down for us at great celerity,” Chase would recall—at about three knots. The whale smashed head-on into the ship with “such an appalling and tremendous jar, as nearly threw us all on our faces.”

The whale passed underneath the ship and began thrashing in the water. “I could distinctly see him smite his jaws together, as if distracted with rage and fury,” Chase recalled. Then the whale disappeared. The crew was addressing the hole in the ship and getting the pumps working when one man cried out, “Here he is—he is making for us again.” Chase spotted the whale, his head half out of water, bearing down at great speed—this time at six knots, Chase thought. This time it hit the bow directly under the cathead and disappeared for good.

The water rushed into the ship so fast, the only thing the crew could do was lower the boats and try fill them with navigational instruments, bread, water and supplies before the Essex turned over on its side.

Pollard saw his ship in distress from a distance, then returned to see the Essex in ruin. Dumbfounded, he asked, “My God, Mr. Chase, what is the matter?”

“We have been stove by a whale,” his first mate answered.

Another boat returned, and the men sat in silence, their captain still pale and speechless. Some, Chase observed, “had no idea of the extent of their deplorable situation.”

The men were unwilling to leave the doomed Essex as it slowly foundered, and Pollard tried to come up with a plan. In all, there were three boats and 20 men. They calculated that the closest land was the Marquesas Islands and the Society Islands, and Pollard wanted to set off for them—but in one of the most ironic decisions in nautical history, Chase and the crew convinced him that those islands were peopled with cannibals and that the crew’s best chance for survival would be to sail south. The distance to land would be far greater, but they might catch the trade winds or be spotted by another whaling ship. Only Pollard seemed to understand the implications of steering clear of the islands. (According to Nathaniel Philbrick, in his book In the Heart of the Sea: The Tragedy of the Whaleship Essex, although rumors of cannibalism persisted, traders had been visiting the islands without incident.)

Thus they left the Essex aboard their 20-foot boats. They were challenged almost from the start. Saltwater saturated the bread, and the men began to dehydrate as they ate their daily rations. The sun was ravaging. Pollard’s boat was attacked by a killer whale. They spotted land—Henderson Island—two weeks later, but it was barren. After another week the men began to run out of supplies. Still, three of them decided they’d rather take their chances on land than climb back into a boat. No one could blame them. And besides, it would stretch the provisions for the men in the boats.

|

| The whaleship Essex, “stove by a whale” in 1821. |

Over the coming week, three more sailors died, and their bodies were cooked and eaten. One boat disappeared, and then Chase’s and Pollard’s boats lost sight of each other. The rations of human flesh did not last long, and the more the survivors ate, the hungrier they felt. On both boats the men became too weak to talk. The four men on Pollard’s boat reasoned that without more food, they would die. On February 6, 1821—nine weeks after they’d bidden farewell to the Essex—Charles Ramsdell, a teenager, proposed they draw lots to determine who would be eaten next. It was the custom of the sea, dating back, at least in recorded instance, to the first half of the 17th century. The men in Pollard’s boat accepted Ramsdell’s suggestion, and the lot fell to young Owen Coffin, the captain’s first cousin.

Pollard had promised the boy’s mother he’d look out for him. “My lad, my lad!” the captain now shouted, “if you don’t like your lot, I’ll shoot the first man that touches you.” Pollard even offered to step in for the boy, but Coffin would have none of it. “I like it as well as any other,” he said.

Ramsdell drew the lot that required him to shoot his friend. He paused a long time. But then Coffin rested his head on the boat’s gunwale and Ramsdell pulled the trigger.

“He was soon dispatched,” Pollard would say, “and nothing of him left.”

By February 18, after 89 days at sea, the last three men on Chase’s boat spotted a sail in the distance. After a frantic chase, they managed to catch the English ship Indian and were rescued.

Three hundred miles away, Pollard’s boat carried only its captain and Charles Ramsdell. They had only the bones of the last crewmen to perish, which they smashed on the bottom of the boat so that they could eat the marrow. As the days passed the two men obsessed over the bones scattered on the boat’s floor. Almost a week after Chase and his men had been rescued, a crewman aboard the American ship Dauphin spotted Pollard’s boat. Wretched and confused, Pollard and Ramsdell did not rejoice at their rescue, but simply turned to the bottom of their boat and stuffed bones into their pockets. Safely aboard the Dauphin, the two delirious men were seen “sucking the bones of their dead mess mates, which they were loath to part with.”

The five Essex survivors were reunited in Valparaiso, where they recuperated before sailing back for Nantucket. As Philbrick writes, Pollard had recovered enough to join several captains for dinner, and he told them the entire story of the Essex wreck and his three harrowing months at sea. One of the captains present returned to his room and wrote everything down, calling Pollard’s account “the most distressing narrative that ever came to my knowledge.”

Years later, the third boat was discovered on Ducie Island; three skeletons were aboard. Miraculously, the three men who chose to stay on Henderson Island survived for nearly four months, mostly on shellfish and bird eggs, until an Australian ship rescued them.

Once they arrived in Nantucket, the surviving crewmen of the Essex were welcomed, largely without judgment. Cannibalism in the most dire of circumstances, it was reasoned, was a custom of the sea. (In similar incidents, survivors declined to eat the flesh of the dead but used it as bait for fish. But Philbrick notes that the men of the Essex were in waters largely devoid of marine life at the surface.)

Captain Pollard, however, was not as easily forgiven, because he had eaten his cousin. (One scholar later referred to the act as “gastronomic incest.”) Owen Coffin’s mother could not abide being in the captain’s presence. Once his days at sea were over, Pollard spent the rest of his life in Nantucket. Once a year, on the anniversary of the wreck of the Essex, he was said to have locked himself in his room and fasted in honor of his lost crewmen.

By 1852, Melville and Moby-Dick had begun their own slide into obscurity. Despite the author’s hopes, his book sold but a few thousand copies in his lifetime, and Melville, after a few more failed attempts at novels, settled into a reclusive life and spent 19 years as a customs inspector in New York City. He drank and suffered the death of his two sons. Depressed, he abandoned novels for poetry. But George Pollard’s fate was never far from his mind. In his poem Clarel he writes of

A night patrolman on the quay

Watching the bales till morning hour

Through fair and foul. Never he smiled;

Call him, and he would come; not sour

In spirit, but meek and reconciled:

Patient he was, he none withstood;

Oft on some secret thing would brood.

Photos: Wikipedia

Read More

http://blogs.smithsonianmag.com

These Realistic-Looking Leather Shoes Are Actually Made of Chocolate, Cost More Than Real Shoes

The “Gentleman’s Radiance” chocolate line is the creation of master chocolatier Motohiro Okai of Rihga Royal Hotel’s chocolate boutique L’éclat, in Osaka, Japan. Each leather show measures 26 centimeters (10.2 inches) in length, and is crafted exclusively from chocolate, including the insole and laces. The shoes come in three different shades of brown leather – light, dark and red-brown – and have a realistic shiny finish which Okai achieved after a painstaking process of trial and error.

Each pair of life-size chocolate shoes comes bundled with shoe care accessories, including a shiny shoehorn made from chocolate and a jar of “shoe cream” that actually contains round disks of tempered chocolate.

The workmanship and attention to detail that went into creating the Gentleman’s Radiance chocolate shoes is best reflected by the obscene price tag of a pair – 29,160 yen (US$258.45). Only nine pairs will be made available for purchase, and only by reservation.

If you’re actually considering spending more money on a pair of chocolate shoes than most people spend for actual footwear, you should know that reservations for the Gentleman’s Radiance line will be accepted between January 20 – February 7, with deliveries for 7-14 February, in time of Valentine’s Day.

More OWLS [via Nina Reznick]

LITTLE KNOWN TIDBIT OF NAVAL HISTORY... via Pat Francke

The U.S.S. Constitution (Old Ironsides—even though she was made of oak), as a combat vessel, carried 48,600 gallons of fresh water for her crew of 475 officers and men. This was sufficient to last six months of sustained operations at sea. She carried no evaporators (i.e. fresh water distillers). However, let it be noted that according to her ship's log, "On July 27, 1798, the U.S.S. Constitution sailed from Boston with a full complement of 475 officers and men, 48,600 gallons of fresh water, 7,400 cannon shot, 11,600 pounds of black powder and 79,400 gallons of rum."

Her mission: "To destroy and harass English shipping."

Making Jamaica on 6 October, she took on 826 pounds of flour and 68,300 gallons of rum. Then she headed for the Azores , arriving there 12 November.. She provisioned with 550 pounds of beef and 64,300 gallons of Portuguese wine.

On 18 November, she set sail for England.

In the ensuing days she defeated five British men-of-war ships, and captured and scuttled 12 English merchant ships, salvaging only the rum aboard each.

By 26 January, her powder and shot were exhausted.

Nevertheless, although unarmed she made a night raid up the Firth of Clyde in Scotland .. Her landing party captured a whisky distillery and transferred 40,000 gallons of single malt Scotch aboard by dawn. Then she headed home.

The U. S. S. Constitution arrived in Boston on 20 February 1799,

with no cannon shot, no food, no powder, no rum, no wine, no whisky, and 38,600 gallons of water.

GO NAVY!

OWLS [via Nina Reznick]

Not Falcons (nor Patriots), these superb owls hail from Europe, Asia, North and South America, captured in photos both recent and more than a century old.

-

A white-faced owl photographed at the Photokina fair on September 21, 2010 in Cologne, Germany.EyesWideOpen / Getty

A white-faced owl photographed at the Photokina fair on September 21, 2010 in Cologne, Germany.EyesWideOpen / Getty

-

A burrowing owl stands on the Olympic Golf Course in Rio de Janeiro during a practice session for the 2016 Summer Olympics on September 8, 2016.Andrew Boyers / Reuters

A burrowing owl stands on the Olympic Golf Course in Rio de Janeiro during a practice session for the 2016 Summer Olympics on September 8, 2016.Andrew Boyers / Reuters -

A few snowflakes melt on the face of Cloudy, a snowy owl, during the cold blustery winter day at the Buffalo Zoo in Buffalo, New York, on January 28, 2004.David Duprey / AP

A few snowflakes melt on the face of Cloudy, a snowy owl, during the cold blustery winter day at the Buffalo Zoo in Buffalo, New York, on January 28, 2004.David Duprey / AP

-

A female great horned owl on her nest, photographed in 2009.Dennis Demcheck / U.S.G.S.

A female great horned owl on her nest, photographed in 2009.Dennis Demcheck / U.S.G.S.

-

A charming wooden escalator in the iconic Macy's department store in Manhattan.

This antique people-mover, built by the Otis Elevator Company ,(which pioneered the machinery) between 1920 and 1930, is not your average modern escalator. With a distinctive Art Deco design and a Steampunk/Dieselpunk feel, it's a unique experience that transports you to a bygone era.

These wooden escalators can still be found in good working condition at Macy's Herald Square, the world's largest department store.

When the store underwent major renovations in 2015, many of its old-world features were upgraded to their modern versions. However, a few wooden escalators stayed put.

The nearly century-old escalators were made of sturdy oak and ash, wood that’s traditionally used in hardwood flooring. The mechanical parts have, of course, been upgraded, and modern safety measures have been put in place.

As of October 2016, the wooden slatted escalators on the lower floors were replaced with metal stairs, only the top 2 floors remain wooden. All wonder how long they'll last.

Via History Daily Org

Photograph ©2022 by Brian Cohen.

Plaster cast of a Roman child's face, Paris, France, 1878-1920

Plaster cast of a child's face, from a mould accidently made when the cement seal of the sarcophagus leaked inside and covered the child's face, found in France in 1878, Roman, 1st century AD, cast 1878-1920

The handwritten French label on the reverse of this tiny plaster cast explains its history. In 1878, a stone Roman burial sarcophagus was found in the gardens of a Paris convent. When a tiny Roman child died 1800 years before, cement sealing the sarcophagus leaked inside and formed a mould of the child’s face. This plaster cast was created using that mould sometime between its discovery and 1920. The translation states the child was buried with a perfectly preserved small glass bottle. However, there is no indication of the cause of death.

The label indicates the child came from Arènes de Lutèce, a prosperous and important Gallo-Roman town within modern day Paris. The Roman remains of Arènes de Lutèce were rediscovered in the 1860s during excavations for the building of a new tram stop.

Men Are Just Happier People --

What do you expect from such simple creatures?

NICKNAMES

• If Laura, Kate and Sarah go out for lunch, they will call each other Laura, Kate and Sarah.

• If Mike, Dave and John go out, they will affectionately refer to each other as Fat Boy, Bubba and Wildman.

EATING OUT

• When the bill arrives, Mike, Dave and John will each throw in $20, even though it's only for $42.50. None of them will have anything smaller and none will actually admit they want change back.

• When the girls get their bill, out come the pocket calculators.

MONEY

• A man will pay $2 for a $1 item he needs.

• A woman will pay $1 for a $2 item that she doesn't need but it's on sale.

BATHROOMS

• A man has six items in his bathroom: toothbrush and toothpaste, shaving cream, razor, a bar of soap, and a towel.

• The average number of items in the typical woman's bathroom is 337. A man would not be able to identify more than 20 of these items.

ARGUMENTS

• A woman has the last word in any argument.

• Anything a man says after that is the beginning of a new argument.

FUTURE

• A woman worries about the future until she gets a husband.

• A man never worries about the future until he gets a wife.

MARRIAGE

• A woman marries a man expecting he will change, but he doesn't.

• A man marries a woman expecting that she won't change, but she does.

DRESSING UP

• A woman will dress up to go shopping, water the plants, empty the trash, answer the phone, read a book, and get the mail.

• A man will dress up for weddings and funerals.

NATURAL

• Men wake up as good-looking as they went to bed.

• Women somehow deteriorate during the night.

OFFSPRING

• Ah, children. A woman knows all about her children. She knows about dentist appointments and romances, best friends, favorite foods, secret fears and hopes and dreams.

• A man is vaguely aware of some short people living in the house.

THOUGHT FOR THE DAY

A married man should forget his mistakes. There's no use in two people remembering the same thing!

SO, send this to the women who have a sense of humor and who can handle it .... and to the men who will enjoy reading it..