Harry and Snowman

Pictured are Harry Deleyer and SnowmanSnowman was an old Amish plow horse that Harry rescued off a truck that was bound for the meat and glue factory for only $80. Less than two years after he rescued Snowman, they rose to become the national show jumping champions and were the Cinderella story and media darlings of the late 1950s and 1960s.

Very few horse stories have been able to truly touch the hearts of a nation. Red Pollard & Seabiscuit did it in the 1930s, Harry deLeyer & Snowman did it in the 1950s and then Ron Turcotte & Secretariat were the last to do it in the 1970s.

HARRY & SNOWMAN (the movie) will be the first time that Harry's remarkable and heartfelt life story will be told by 85-year-old Harry himself.

1955 letter to Marilyn Monroe from John Steinbeck

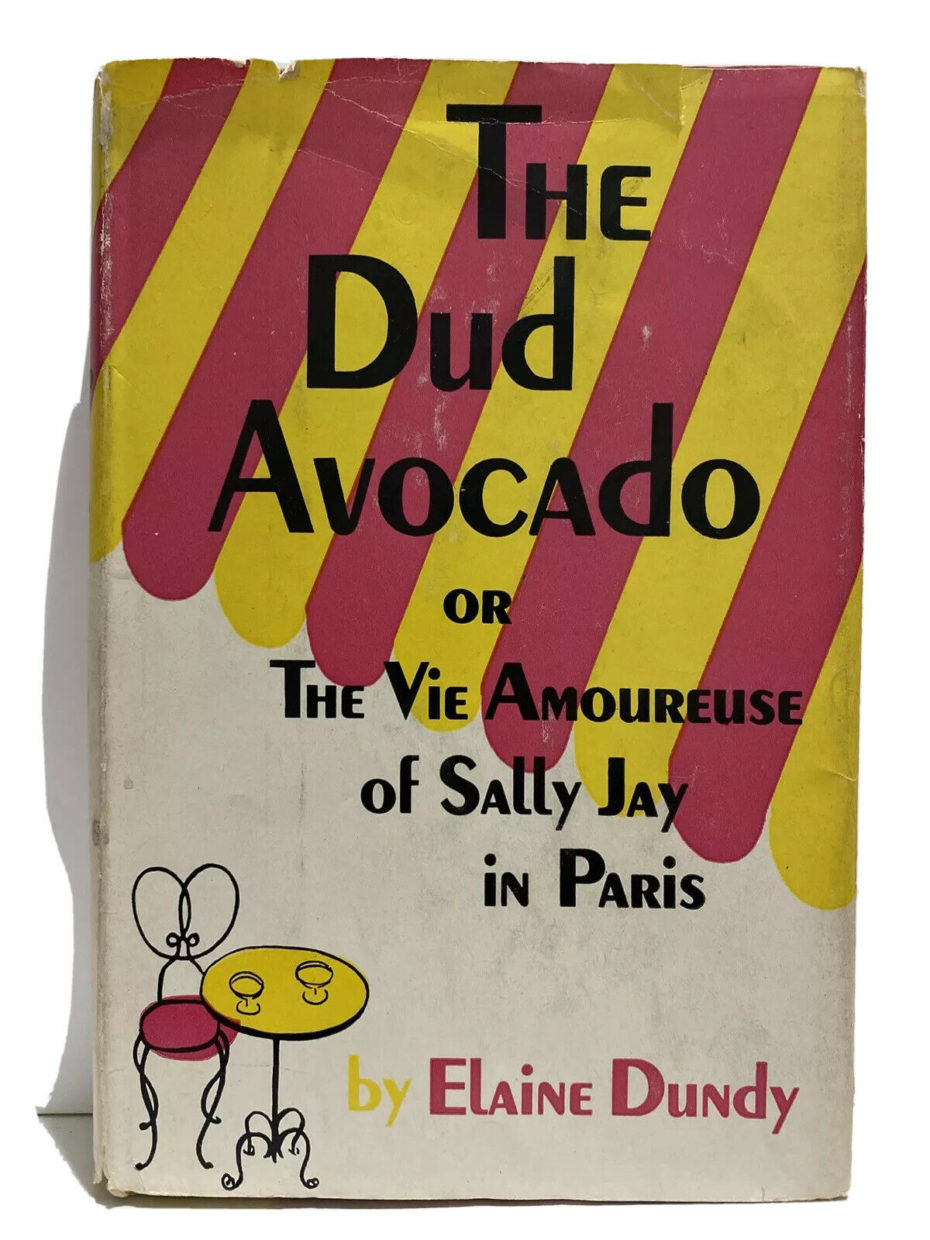

Before There Was Emily in Paris, There Was Sally Jay Gorce

Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century and well into the beginning of the next, it’s easy to track our fascination with young women attempting to figure out life – they are witty, tenacious, and often keenly perceptive of the world in which they exist and their place within it. Their names have become household, pop-culture gospel: Holly, Carrie, and now (for better or worse) Emily. But there is one name on that list that often fails to come up: Sally Jay Gorce.

Now, let’s go back for a moment. In November of 1958, Esquire magazine began serialising a novella that told the story of a young woman living in New York. She was a bit of a party girl, and she was looking for a rich man to make all her dreams come true. What those dreams were, exactly, no-one was really sure. Its author, Truman Capote, had originally sent the story to Harper’s Bazaar, who later backed out on the basis that it was just a bit too risque. As well as being serialised in Esquire, the novella was published in full by Random House. It was called Breakfast at Tiffany’s. By 1961, it had been adapted for the screen into what would become one of the all time greats, Audrey Hepburn stepping into the OG little black dress in a performance that would both irk (one person, Capote, who wanted Marilyn Monroe) and bewitch (everyone else, who, as the saying goes, either wanted to be her or be with her.)

But also in 1958, some nine months before Breakfast at Tiffany’s was published, there was another novel making the rounds, already on its way to becoming a cult favourite. In January of that year, the writer Elaine Dundy – previously an actress in Paris and London, now married to the theatre critic Kenneth Tynan and a new mother – had released her first novel into the world. She called it, rather coyly, The Dud Avocado.

Elaine Dundy based the novel on her own exploits when she lived in Paris for a year before heading to London to act. “All the outrageous things my heroine does, “ Dundy has stated in interviews, “like wearing an evening dress in the middle of the day, are autobiographical. All the sensible things she does are not.” Groucho Marx, who loved the book, sent her a note: “If this was actually your life, I don’t see how the hell you ever got through it.”

Dundy’s method of using her own life as a springboard is similar to that of another woman several decades later, who in November of 1994 began writing a column for the New York Observer detailing the exploits of her and friends as young women making a life – “Well, but living you know…” – in the Big Apple. She called the column Sex and the City.

In Memoriam

The Flying Housewife

Geraldine “Jerrie” Mock became the first woman in history to fly solo around the world on this day in 1964. Nicknamed "the flying housewife" by the press, Mock circumnavigated the Earth flying a Cessna 180 single-engine monoplane; 27 years after Amelia Earhart's famous and ill-fated attempt. Despite her incredible record-making feat, Mock's name is largely unknown today.

In an interview before her death, the Ohio native said, “I did not conform to what girls did. What the girls did was boring.” At age 7, after taking a short airplane ride at a nearby airport, Mock declared she wanted to be a pilot. Several years later, following Amelia Earhart’s adventures on the radio, she dreamed of making similar flights. “I wanted to see the world,” she remembered. “I wanted to see the oceans and the jungles and the deserts and the people.”

She was the only woman in the aeronautical engineering class at Ohio State University, where the male students left her alone after she got the only perfect score on a difficult chemistry exam. But in 1945, women rarely pursued aeronautics careers, and at the age of 20, she dropped out of college to marry Russell Mock. Soon, Mock was busy with her role as wife and mother of three, but she still dreamed of flying. Once her oldest children were in school, she started taking flying lessons and earned her pilot's license. When Mock tired of her ordinary life at home, she complained to her husband about being bored. “Maybe you should get in your plane and just fly around the world,” he joked, but Mock decided he was right.

She spent a year preparing for a round-the-world flight, helped by fellow pilots and navigators who thought she was crazy to want to undertake such a dangerous endeavor. At the age of 38, she began her flight on March 19, 1964 -- two days after another woman, Joan Merriam Smith, also departed on a solo round-the-world attempt.

Mock never wanted to capitalize on her fame, preferring solitude and quiet: “The kind of person who can sit in an airplane alone is not the type of person who likes to be continually with other people,” she explained. After 1969, finances prevented her from ever flying an airplane again. And while she recognized the significance of her flight, achieving the record was not as important as the joy she took in flying. In interviews on her various stops during the flight, she demurely said, “I just wanted to have a little fun in my airplane.” Jerrie Mock passed away in 2014 at the age of 88.