Every project has its own clock!

~ Ken Atchity

Every project has its own clock!

~ Ken Atchity

Listen to Dr. Ken Atchity reframe rejection as an illusion we can see past, instead of the unmovable barrier. It matters. Find out why.

“Whether you succeed or not is irrelevant — there is no such thing, making your unknown known is the important thing — and keeping the unknown always beyond you.”

Georgia O’Keeffe counseled Sherwood Anderson in her 1923 letter of advice on being an artist.

Mentoring Matters - Developing A Career: Learning To Identify The Story You Want And Go After It |

| By Kia Kiso, |

I have more than 90 credits as an AC/Loader, Telecine Colorist and VFX Coordinator, but eight years ago I heeded my lifelong calling to produce. Since then I have shepherded award-winning videos, promos for CBS and launched two feature documentaries on Netflix. In 2013 I joined the PGA because I knew of its many benefits, and I wanted to be part of a community of like-minded creatives. Currently I have focused on building my production company to develop fictional content, with an aim at creating compelling and unique stories in order to make the world a better place. When I applied to the 2016 PGA Mentoring Program, I had just walked away from the option on a book into which I had put a lot of time and resources. I was disappointed and wished I could have saved the project. The experience led me to realize that development was an aspect of producing I was less familiar with. I was looking for expert advice on how to assess opportunities, set up a project for success, handle relationships with authors, lawyers and talent, and run a production company. Thankfully the PGA Mentoring Program paired me with producer Ken Atchity. I was thrilled to be matched with Ken for a lot of reasons, among them his industry experience and teaching background. However I admit, I was especially attracted to his philosophy—“I believe in the power of stories to change the world.” Our first connection was an in-person, 90-minute meeting, in which he gave me feedback on a particular project of mine. Ken had some great advice about pitching—if a project tackles potentially controversial or delicate issues, Ken advised weaving some well-researched statistics or facts into the pitch to send the message that the material wouldn’t suggest a problem for the network and lead to a premature no. He wrapped up the meeting saying I could contact him about the project at any time, even after the mentorship ends. Very generous. Since that first meeting, we’ve had a pivotal phone conversation during which he suggested I was in a great position to go after an option I was very excited about, helping me to design a strategy on how to move forward quickly—starting with enhancing my relationship with the rights owner. He’s been ready to answer any questions by email. Even as recently as this morning, we were in touch to discuss a lunch I was preparing for with a writer who wanted to work with me. Ken has been wonderful. He celebrates my triumphs and brainstorms solutions to my challenges. I am very grateful for his willingness to participate in the Mentoring Program and to the Producers Guild for providing it |

BIG Congratulations to the talented Justin Allen Price Voice Over WINNER of the One Voice Award for best performance of an audiobook/fiction for his narration of Story Merchant Book's Talmadge Farm by Leo Daughtry - Author - Talmadge Farm!

You can now LISTEN to Talmadge Farm on Audible!

This cat door is considered the oldest on record. Installed in 1598, the cat door allowed cats to enter and hunt mice and rats, which were drawn to the lubricated animal fat applied to the mechanics of a large astronomical clock.

Tobe Roberts joins Kevin Smith's 55th Birthday Bash at his comic book store, Jay and Silent Bob's Secret Stash in Red Bank, New Jersey.

In Japan, ancient quarry sites still preserve fascinating traces of how people once cut and shaped massive stones. At many of these sites, you’ll notice neat rows of small square holes carved into the rock—these are wedge sockets, the result of a technique where workers drove wooden or metal wedges into the stone to split it along a straight line. It was a smart and straightforward method that let them carefully control the break and create smooth, uniform blocks.

There’s also evidence that an even older method might have been used. In this technique, dry wooden wedges were inserted into cracks, then soaked with water. As the wood expanded, it slowly forced the rock apart. This approach was also seen in ancient Egypt and other civilizations.

What’s especially intriguing is that Japan has many of these prehistoric stone-working sites, even though its written history only dates back about 1,600 years. This points to a much older and largely unknown tradition of stone craftsmanship. Some of the remaining stone foundations suggest that impressive structures once stood there—now lost to time, earthquakes, or both

|

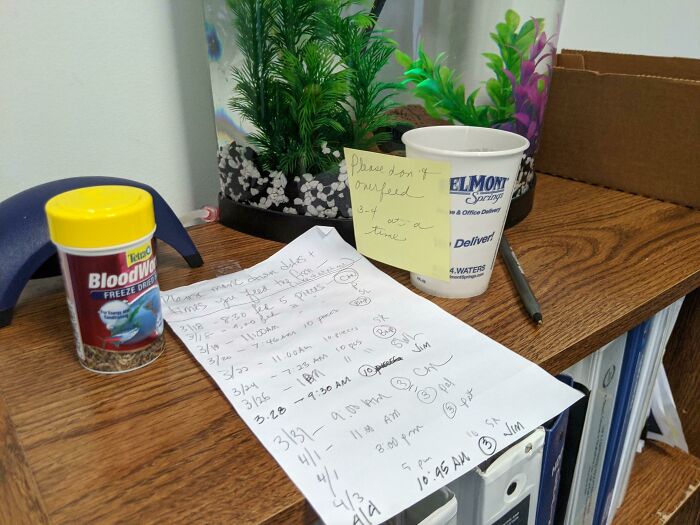

This person asked their coworkers to help feed their fish in the office while they were stuck working at home. Not only did one person volunteer, but it looks like the whole office signed up to help! His coworkers, to his delight and amazement, took this seriously and kept track of it in a logbook.

It’s impossible to overestimate the importance of working with intelligent people. The logbook isn’t just cute, but an important safety measure alongside the note on the cup reading, “Please don’t overfeed.” The fish’s owner must have appreciated the level of care their coworkers put into feeding the fish.

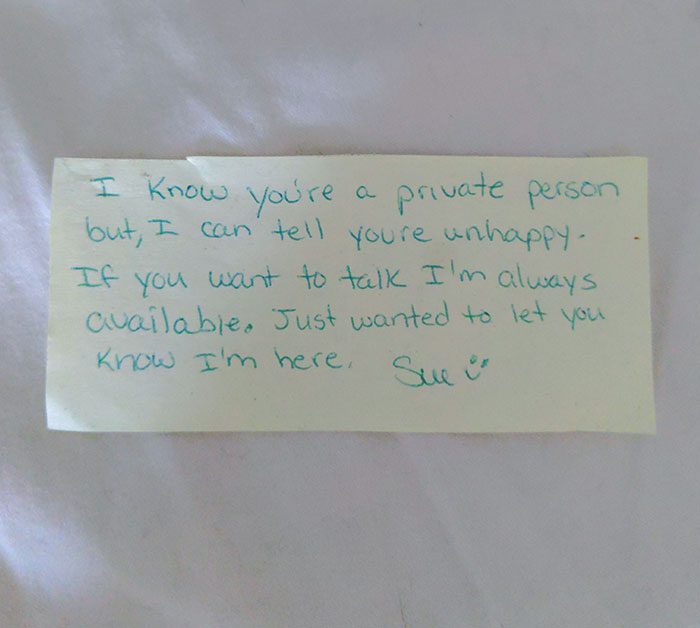

Something as simple as a sticky note can make all the difference to someone going through a rough time. The coworker that left this note must have a big heart to recognize when someone isn’t happy but still respects their personal space with a small yet grand gesture.

It took us a minute to process this image. Why is a construction worker digging a wholesome gesture? Well, take a look at the umbrella over his head. And, look at how it’s held up. This kind gesture deserves to be recognized.

You might not understand the caption “I’m a nice colleague” if you haven’t properly understood the image. A coworker came up with a way to protect their colleague from the elements while they were digging. We can only assume that the job required only one of them to be laboring outside, for this little setup to occur.

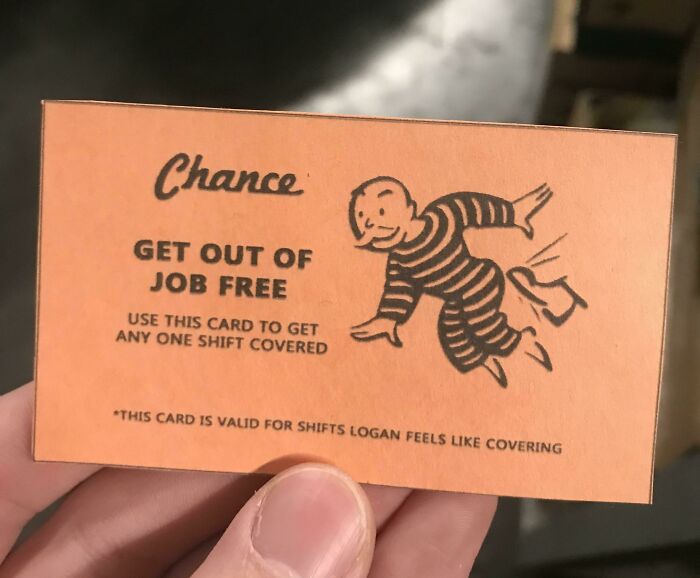

What could be a better birthday present than a free pass to get away from work whenever you want? Without thinking, we might choose this over a box of cupcakes However, we hope no one asks us to choose between the two, especially if the cupcakes are red velvet.

This is a fantastic concept for anyone who works in a shift-based environment. On your coworker’s birthday, you can give them an access card to use to get away from work. It’s crucial, though, that the receiver understands that the card is only good for the shift you’re willing to cover.

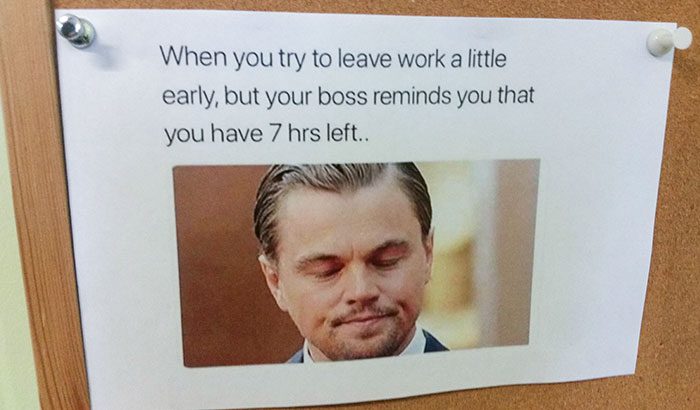

This is by far the most amusing thing we’ve ever seen. This 66-year-old receptionist devotes their time and resources to making their coworkers happy. Even if work is chaotic, no one will be able to look at this and not grin. It reminds them that they are all in this together.

However, we’re curious as to what the employer thinks of this and other memes found on their receptionist’s desk. This is a fantastic way to get everyone in the office in a good attitude. We’ll always stroll past the receptionist’s desk just to chuckle if we work somewhere like this.

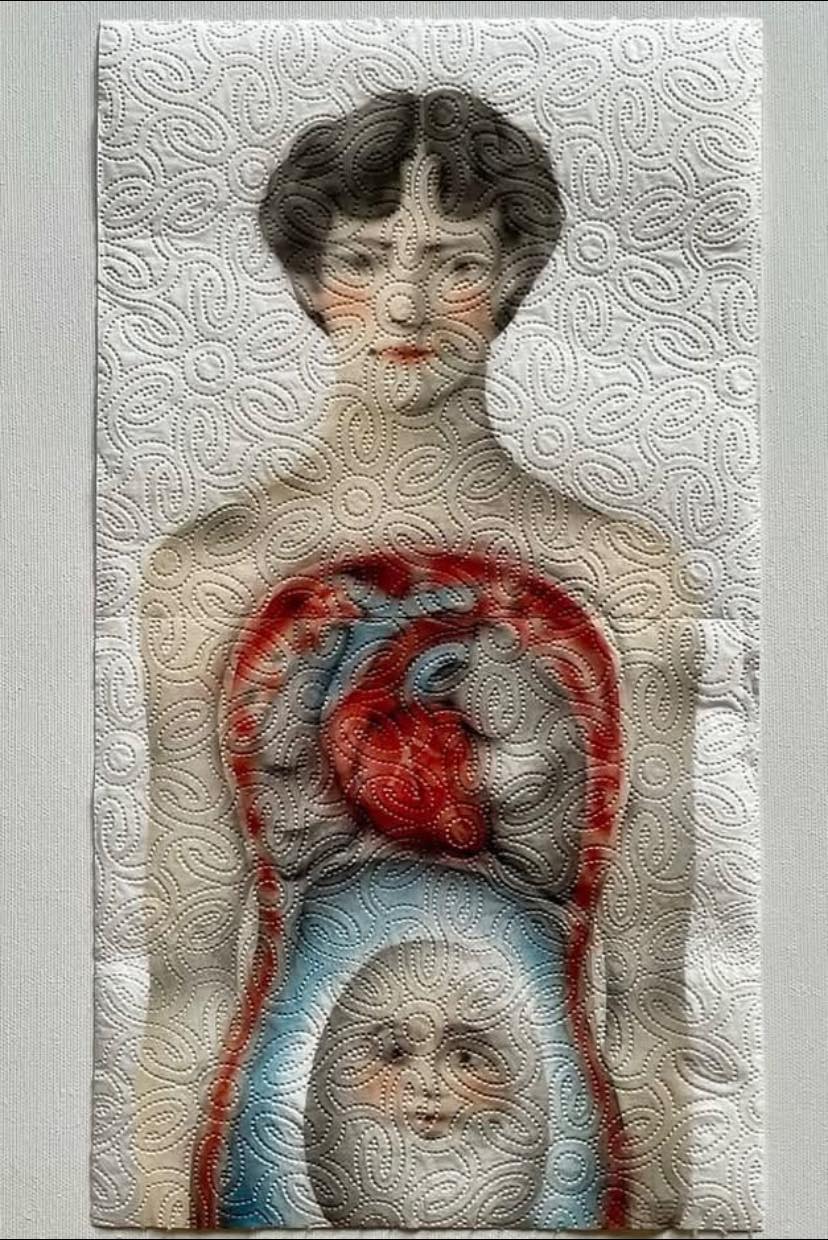

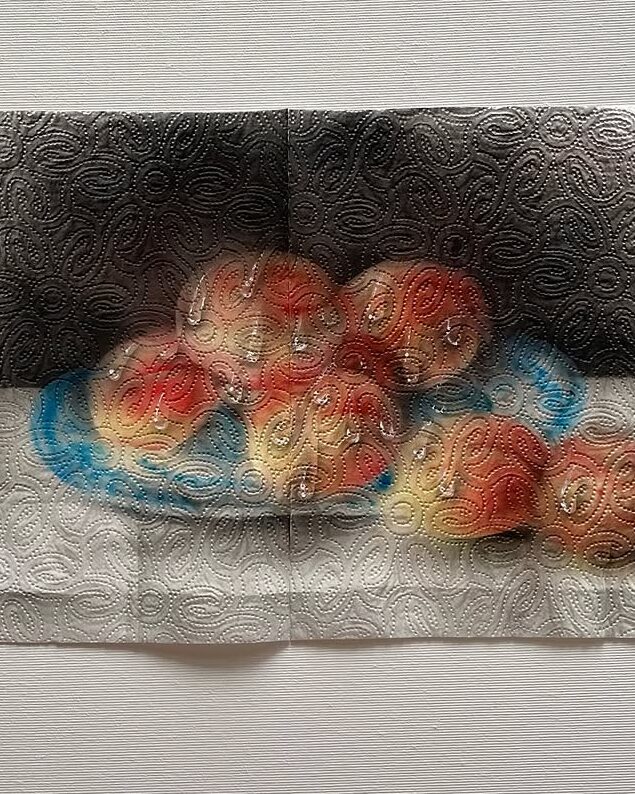

Artist Helena Minginowicz paints fragility via https://www.messynessychic.com/

On the cover: The illustrator Justin Metz borrowed the visual language of old Ray Bradbury and Stephen King paperbacks to portray a circus wagon on its ominous approach to a defiled Capitol. Something Wicked This Way Comes, Bradbury’s 1962 masterpiece, was a particular inspiration. Over the course of The Atlantic's 167-year history, only very rarely have we published a cover without a headline or typography.

"Do

your work. If everyone follows their calling and dedicates themselves to it,

the world will be a better place.”

This insightful interview explores

what began as Kayoko Mitsumatsu’s exploration of yoga philosophy and social

entrepreneurship, which has grown into a global movement. As the founder of Yoga

Gives Back, Kayoko transformed a simple idea—redirecting the cost of one

yoga class—into a powerful nonprofit initiative that funds microloans,

education, and empowerment programs for underserved women and children in

India.

Each year, after visiting all of

the Yoga Gives Back organization’s programs throughout India, Kayoko makes a

meaningful visit to Mother Teresa’s Home in Kolkata. From a young age, she

hoped to volunteer at the Home for the Dying. On one occasion, she spoke with a

sister who had worked closely with Mother Teresa. When she expressed her desire

to serve there, the sister responded, reflecting Mother Teresa’s own wisdom:

“Don’t come here! You’ve already found your mission.“ Kayoko strives to stay

focused on the mission itself rather than the outcomes.

With time, Kayoko came to see YGB’s

work as truly divine. Yoga Gives Back continues to attract extraordinary

individuals who arrive when needed most, helping move YGB mission forward. Our

global family of supporters, Ambassadors, partners,

and donors make our mission possible—embodying this year’s Global Gathering for India's mantra, Unity in

Action. Every step we take together helps transform gratitude into action

every day.

A Circle of Impact—Thanks to You

Since 2007, Yoga Gives Back has

supported underserved women and children in India—the birthplace of yoga—by

providing:

GET INVOLVED!

Since 421 AD, Venice has stood on millions of tree trunks stuck into the clay bottom of the lagoon. Not steel or concrete, but mostly alder, with a few oaks, support the entire city.

Prevents millions of accidents annually

Prevents millions of accidents annually Is used on every modern vehicle (even spacecraft!)

Is used on every modern vehicle (even spacecraft!) Saves more lives than seatbelts or airbags combined

Saves more lives than seatbelts or airbags combined