Raising the “Beautiful Sea Goddess”

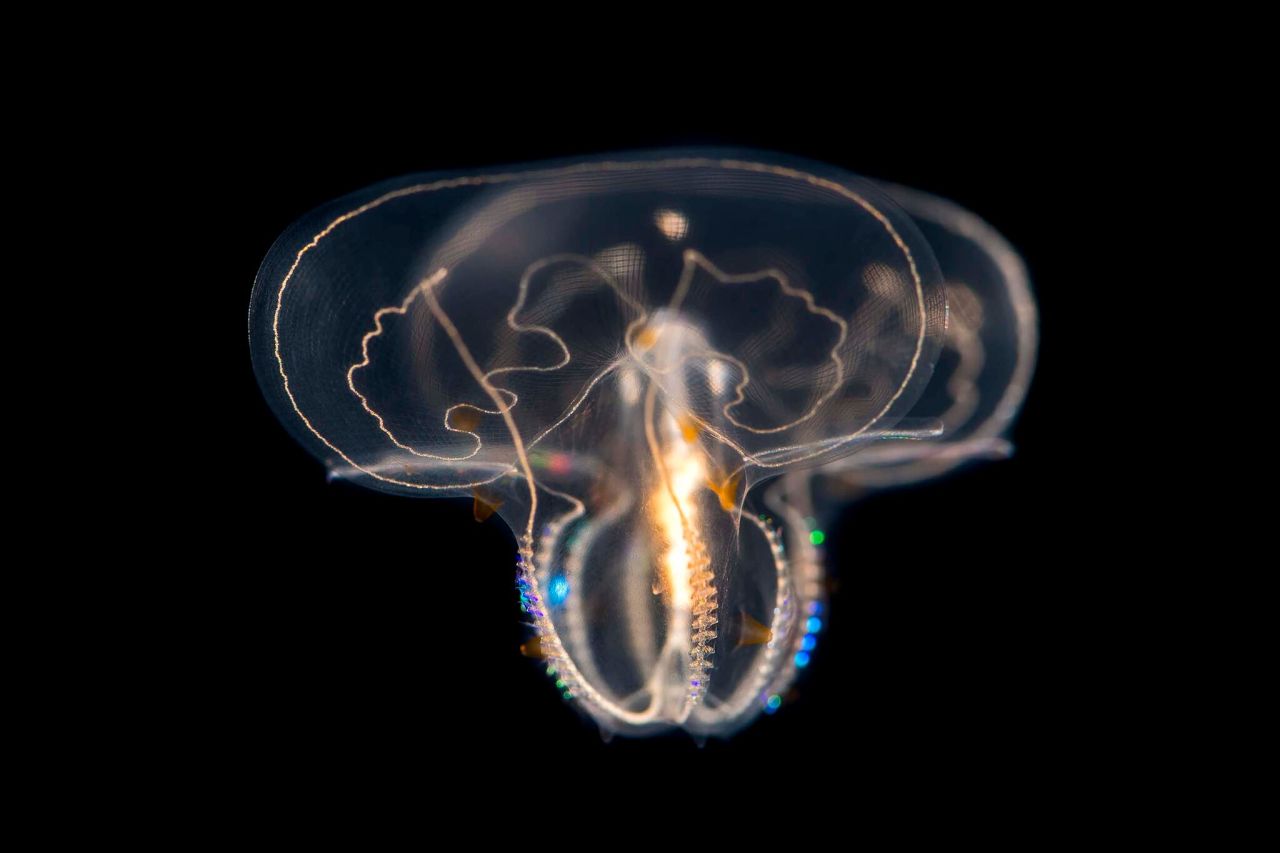

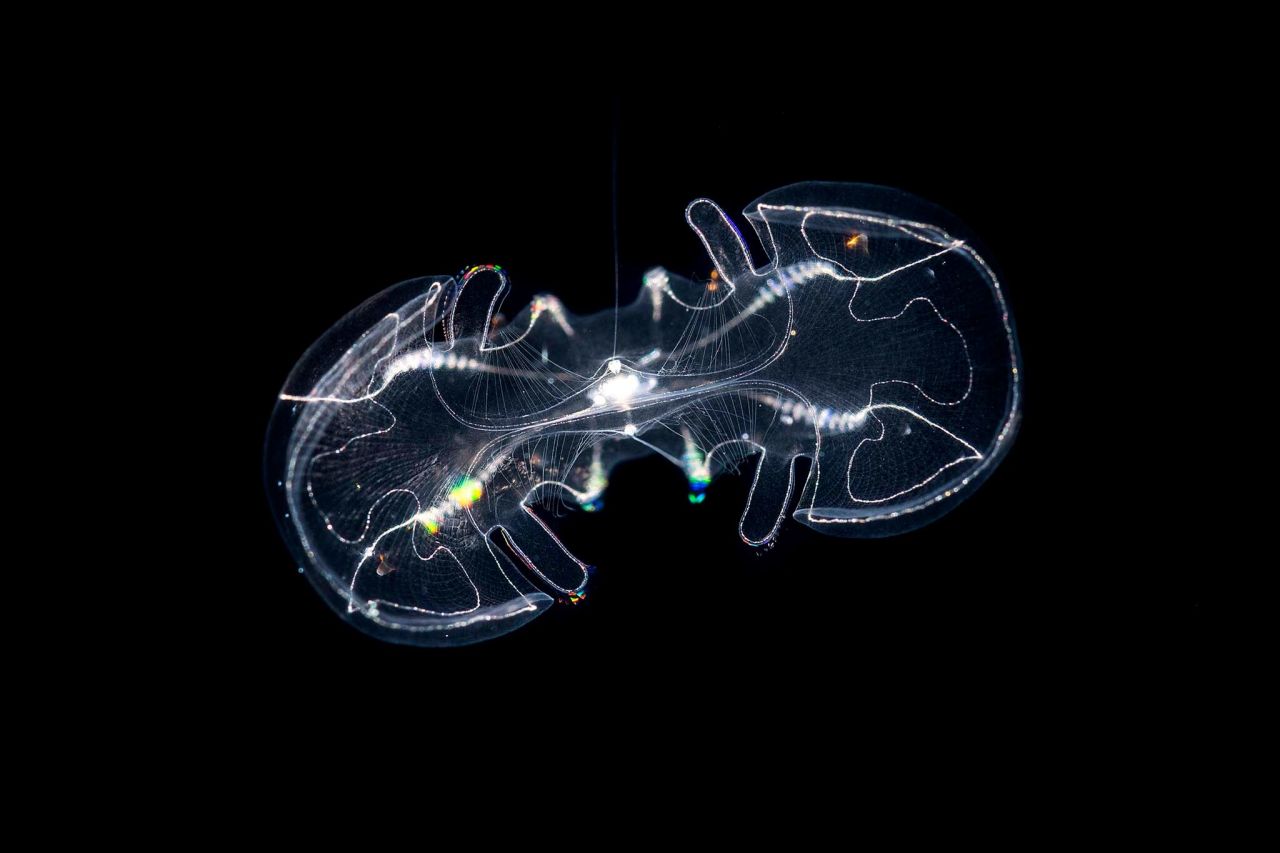

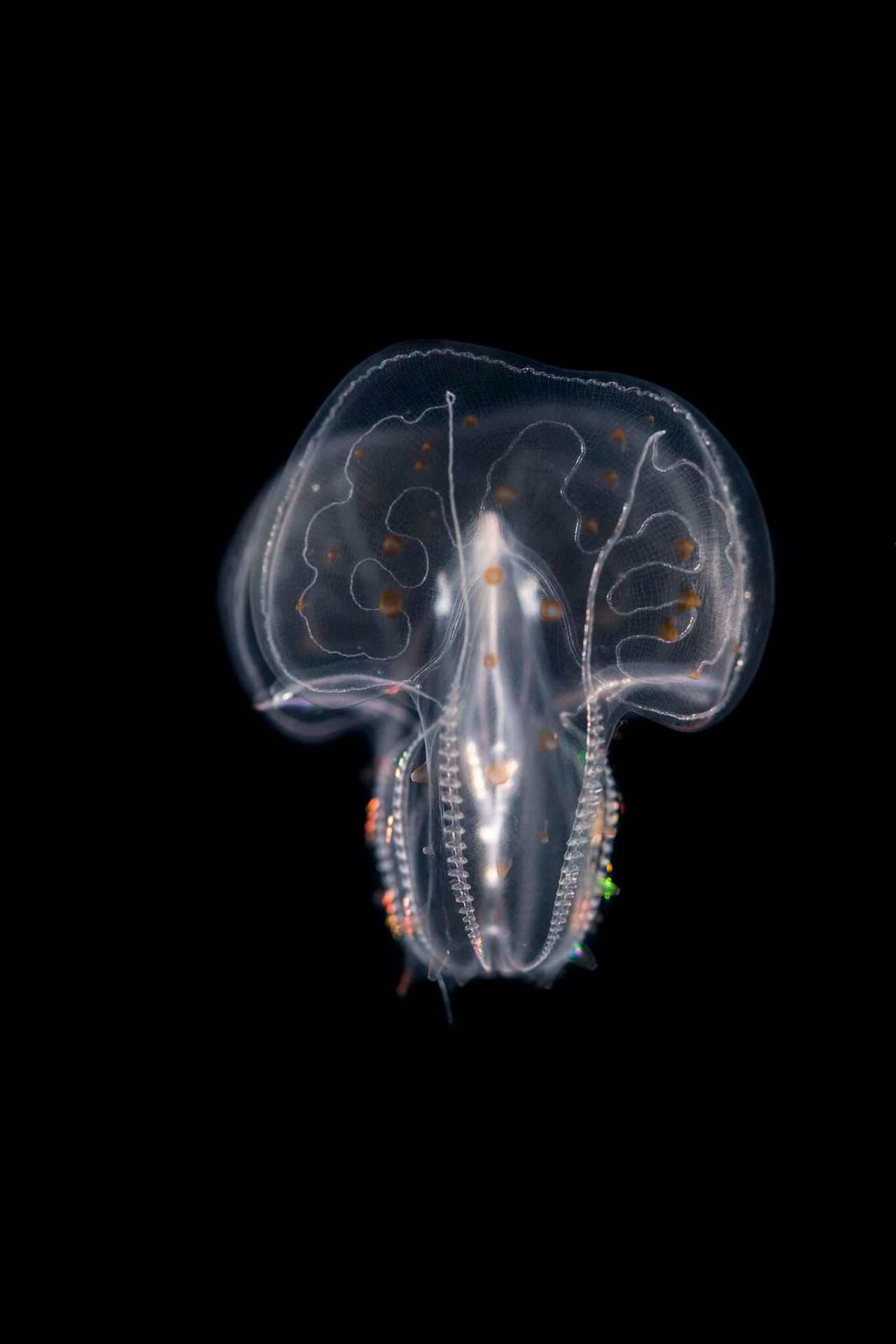

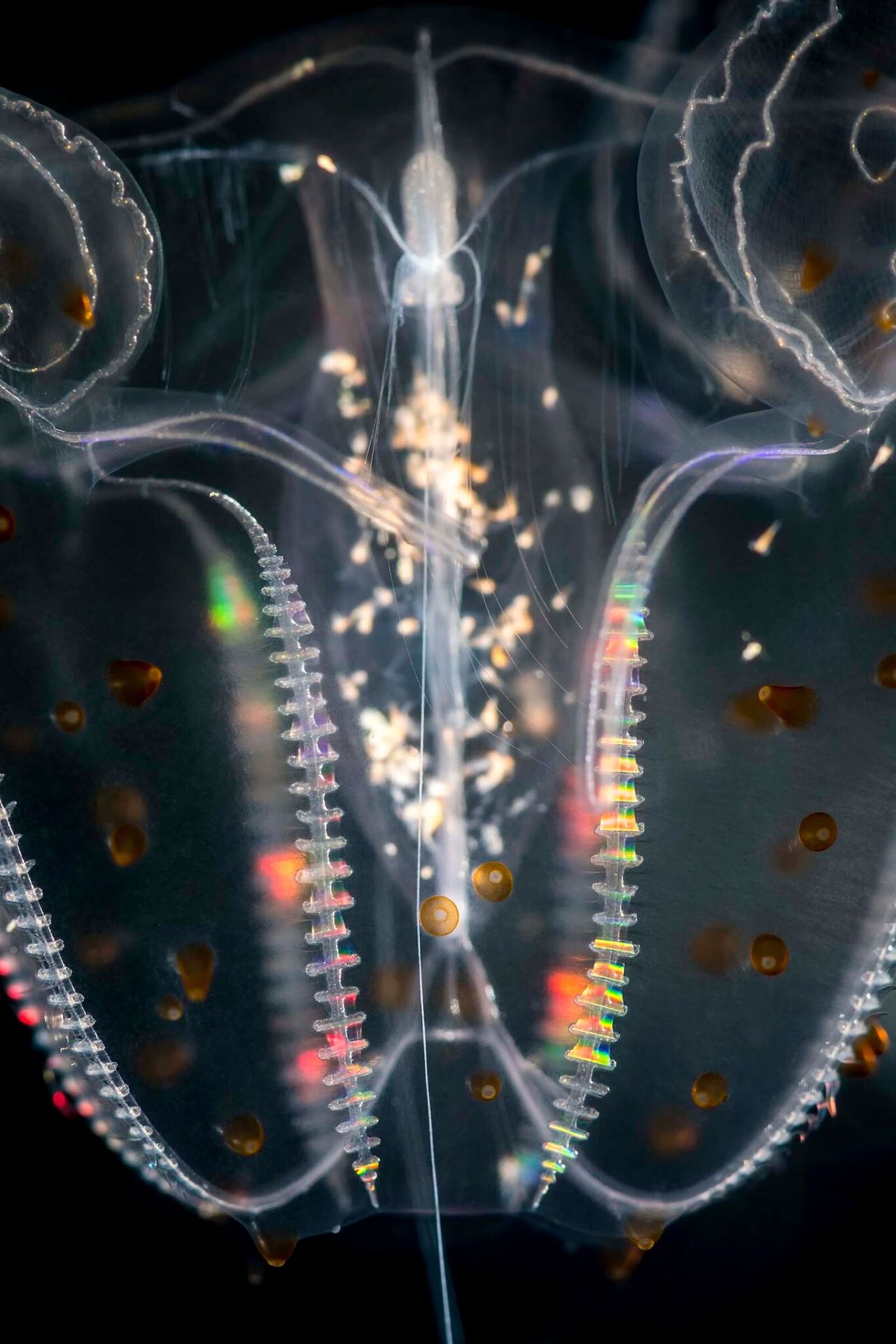

The spotted comb jelly’s common name refers to orange “knobs” or spots along its body.

“They also have cool whips called ‘auricles’ that they wave around—undulate—in this really cool slow wave motion, probably driving food into their mouths,” he says.

‘Barely organized water’

Spotted comb jellies are not endangered, and range from Baja California north to British Columbia. But seeing them in an aquarium is a rare treat, because their extreme fragility makes handling them a dicey proposition.

Wild specimens first went on exhibit in Monterey in 2002, as part of the special exhibition, “Jellies: Living Art.” On rare occasions, and for brief periods, they’ve returned to the exhibit galleries.

To protect the easily broken beauties from perturbations, Wyatt says members of the team “have to move like a sloth. In order to move them we’ve got to get a beaker around them, and that has to be done very, very slowly. We try to get them to swim into the beaker so we don’t have to disturb the water around them.”

Slow-motion exhibit maintenance

Senior Aquarist Wyatt Patry helped unlock the secrets of culturing comb jellies, including Leucothea.

In the wild, they take refuge at depths up to 300 feet below the surface, “to get away from all the waves and the swells and commotion up above,” Wyatt says. But they also show up in Monterey Bay in late fall, when surface waters are warm and calm.

“Over the last two years, we’ve really kind of excelled at comb jelly culture here at the Aquarium,” Wyatt says, “so we were really ready to receive and work with Leucothea immediately.”

Here he credits his partner Tommy Knowles, as well as Michael Howard and MacKenzie Bubel.

The Aquarium now has dozens of spotted comb jellies on hand. Some grew to four inches long in just two months.

Inspired by Homer’s ‘Odyssey’

“It was named by the master’s student, and in deference to her work, I kept the unpublished name,” says George, a senior education and research specialist at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute. The name translates as “beautiful sea goddess.” (In Homer’s “Odyssey”, Leukothea is a sea nymph who rescues Odysseus from drowning.)

“So, it appears that they can be picky eaters, sorting out what each individual prefers,” he says.

That the Aquarium has managed to culture the species is “amazing” to George. “I never had much luck keeping them in captivity for more than a day, so I’m completely gobsmacked.”

“If asked about the possibility, I would’ve estimated less than a 5 percent chance of success—so kudos to the team,” he says.

Successfully culturing a species often opens the door to sharing subsequent generations of offspring with other public aquariums. But Wyatt, having gone to great lengths to put a few on display, doubts it’s realistic in this case. These jellies, he says, are too fragile.

No comments:

Post a Comment