How much did the Titanic menu sell for at auction?

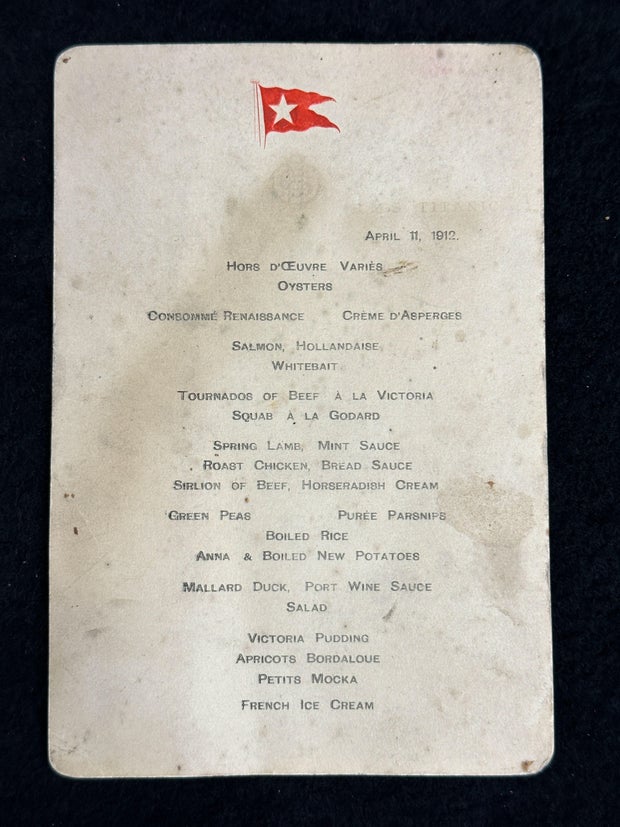

The menu sold for 83,000 British pounds (about $101,600), according to auction house Henry Aldridge and Son Ltd. Dated April 11, 1912, the menu shows what the Titanic's most well-to-do passengers ate for dinner three days before the ship struck an iceberg that caused it to sink in the Atlantic Ocean within hours.

Featuring such dishes as spring lamb with mint sauce, "squab à la godard" and "apricots bordaloue," the menu shows some signs that it was exposed to water. It was found earlier this year among the personal belongings of a Canadian historian who lived in Nova Scotia, where recovery ships brought the remains of those who died in the catastrophe.

A Titanic menu from April 11, 1912, was sold at auction in the U.K.COURTESY HENRY ALDRIDGE AND SON LTD.

A Titanic menu from April 11, 1912, was sold at auction in the U.K.COURTESY HENRY ALDRIDGE AND SON LTD.How the menu came to be in the historian's possession is unknown, according to the auction house. He died in 2017, and his family found the menu tucked away in a photo album from the 1960s.

A pocket watch recovered from a Russian immigrant sold for 97,000 pounds (about $118,700), according to the auction house. Sinai Kantor, 34, was one of the over 1,500 people who died in the disaster. He was immigrating to the U.S. with his wife, Miriam, who survived the tragedy.

A pocket watch recovered from a Titanic victim was sold at auction in the U.K.COURTESY HENRY ALDRIDGE AND SON LTD.

A pocket watch recovered from a Titanic victim was sold at auction in the U.K.COURTESY HENRY ALDRIDGE AND SON LTD.After Kantor's body was recovered from the Atlantic, his belongings were returned to his wife, according to the auction house. The items included his Swiss-made, silver-on-brass pocket watch with Hebrew figures on its heavily stained face.

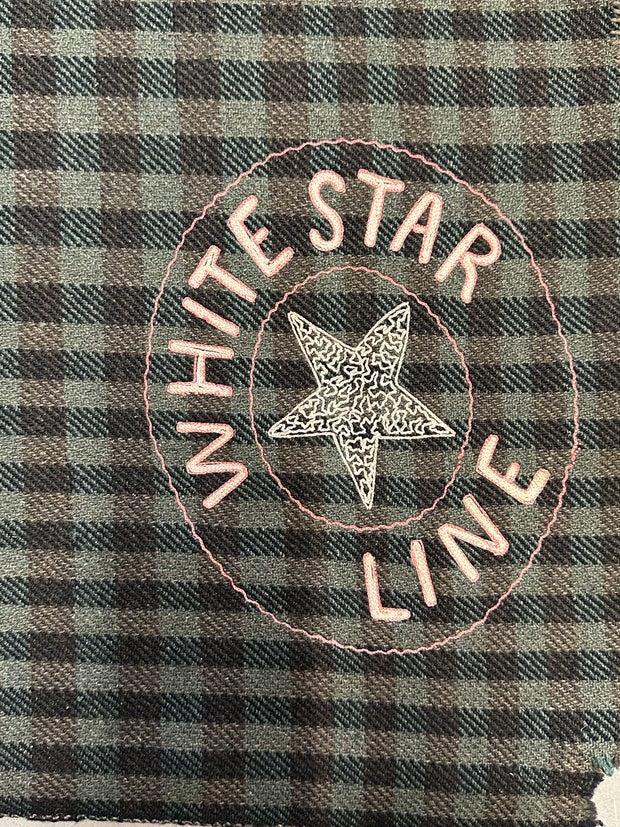

A deck blanket from the Titanic sold for slightly less than the watch at 96,000 pounds (about $117,500), according to the auction house.

The tartan blanket features the logo for White Star Line, the British company that owned and operated the Titanic. The blanket was used on a lifeboat and then taken on a rescue ship to New York, where it was acquired by a White Star official, according to the auction house.

A deck blanket from the Titanic was sold at auction in the U.K.COURTESY HENRY ALDRIDGE AND SON LTD.

A deck blanket from the Titanic was sold at auction in the U.K.COURTESY HENRY ALDRIDGE AND SON LTD.

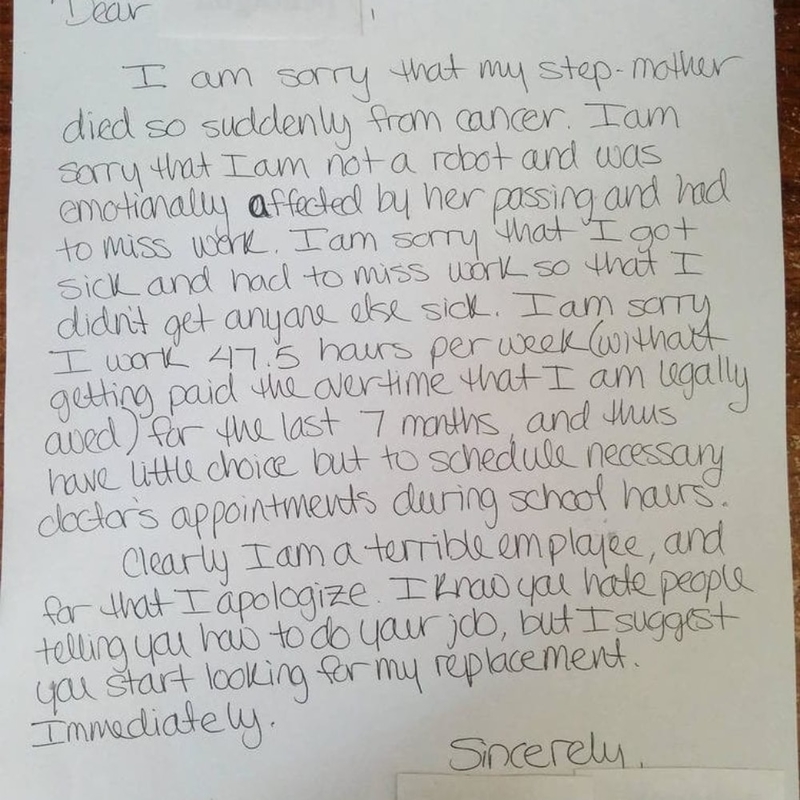

Reddit.com/asardoni

Reddit.com/asardoni Reddit.com/Sinc3rIT

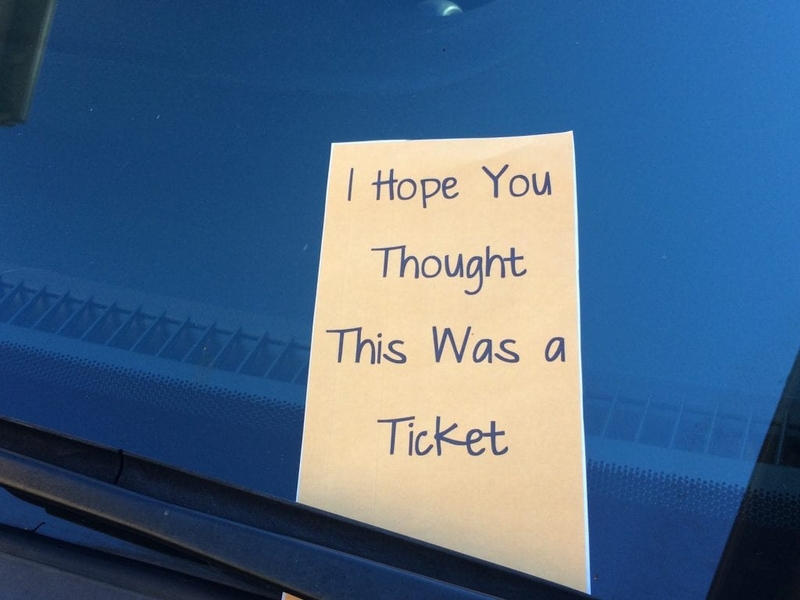

Reddit.com/Sinc3rIT Imgur.com/jBSQM0N

Imgur.com/jBSQM0N Twitter/@saved_a_click

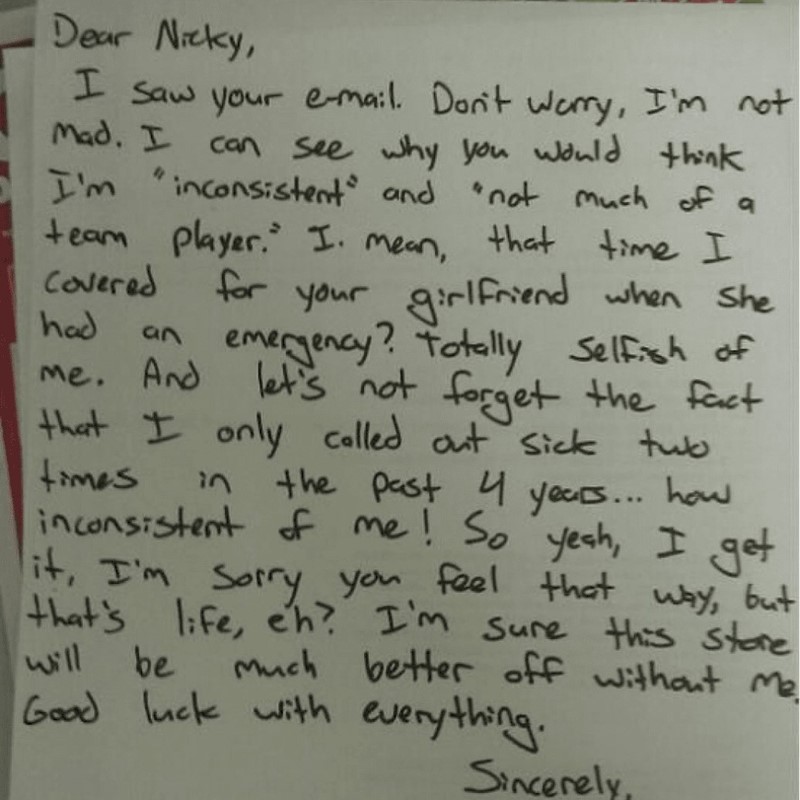

Twitter/@saved_a_click Reddit.com/Pistolfist

Reddit.com/Pistolfist Reddit.com/Leviathin

Reddit.com/Leviathin

.png)