Vanderbilt Ball How a costume ball changed New York elite society

Prior to the ball, Gilded Age New York society had been dominated by the Mrs. Astor. (Emphasis, hers – to even ask which Astor was a sure sign that you were thoroughly ignorant in the most basic points of New York’s social hierarchy.) Mrs. Caroline Schermerhorn Astor and self-appointed “society expert” Ward McAllister were the authorities in all things upper class. It was up to them to decide if your last name was venerable enough or if your bloodlines were pure enough for entry into the upper ranks of society. They were the champions of old money and tradition.

But New York’s social hierarchy is not known for being static. Thanks to the meteoric increase in millionaires in New York due to the Civil War and the Industrial Revolution, many of whose fortunes rivaled or even surpassed the oldest of families, Mrs. Astor and Ward McAllister had a whole new challenge in deciding who of the nouveau riche was acceptable. This led to the creation of the famous List of 400 — the Four Hundred people who were New York’s high society. One family that they deemed wholly unsuitable were the Vanderbilts. The willful crassness of Cornelius “Commodore” Vanderbilt, the ambitious entrepreneurial shipping and railroad industry mogul, and patriarch of the family, was still the stuff of legends.

The Commodore’s grandson, William Kissam Vanderbilt, married the determined, pugilistic and socially ambitious Alva Erksine Smith from Mobile, Alabama (but schooled in Paris). Alva made it her mission to bring the Vanderbilts into what she thought was their proper place in society, and onto the list of the 400.

Her first move? Building an opulent French château style mansion designed by Richard Morris Hunt at 660 Fifth Avenue at 52nd street that literally overshadowed the dour, albeit luxurious, town homes that lined the avenue.

H.N. Tiemann & Co. 1898. 5th Avenue north from 52nd Street. Museum of the City of New York. X2010.11.4755.

As grand as the mansion was, the ball which served as her housewarming party was even grander. On March 26, 1883 Alva threw one of the most incredible parties that New York had ever seen. With her access to seemingly endless amounts of money, she used every available resource – including the power of the press by inviting journalists to come in and preview the decorations before the ball began – to build excitement and to make it bigger than any ball before it. According to an apocryphal tale, Alva used what was possibly the simplest weapon in her arsenal to gain admission to the New York 400: good old fashioned manipulation. The story goes, that like all marriageable young girls Mrs. Astor’s daughter, Carrie, was anxiously awaiting her invitation and even began practicing for a quadrille with her friends. Then the unthinkable happened: all of her friends got their invitations and hers never came. She immediately got her mother on the case. Due to complex social customs, Alva claimed she could not invite Miss Astor since Mrs. Astor had never called on the Vanderbilt home. Mrs. Astor really had no choice but to drop her visiting card at 660 5th Avenue, thus formally acknowledging the Vanderbilts. The Astors’ invitation was received the next day.

At ten in the evening carriages began arriving at 660 5th Avenue, dropping off nearly 1200 outrageously costumed members of the highest ranks of society. Crowds, held back by police, strained to catch glimpses of debutantes and society stalwarts attired in their costumes as they were escorted into the mansion. Even Mrs. Astor (with her daughter) and Ward McAllister were there.

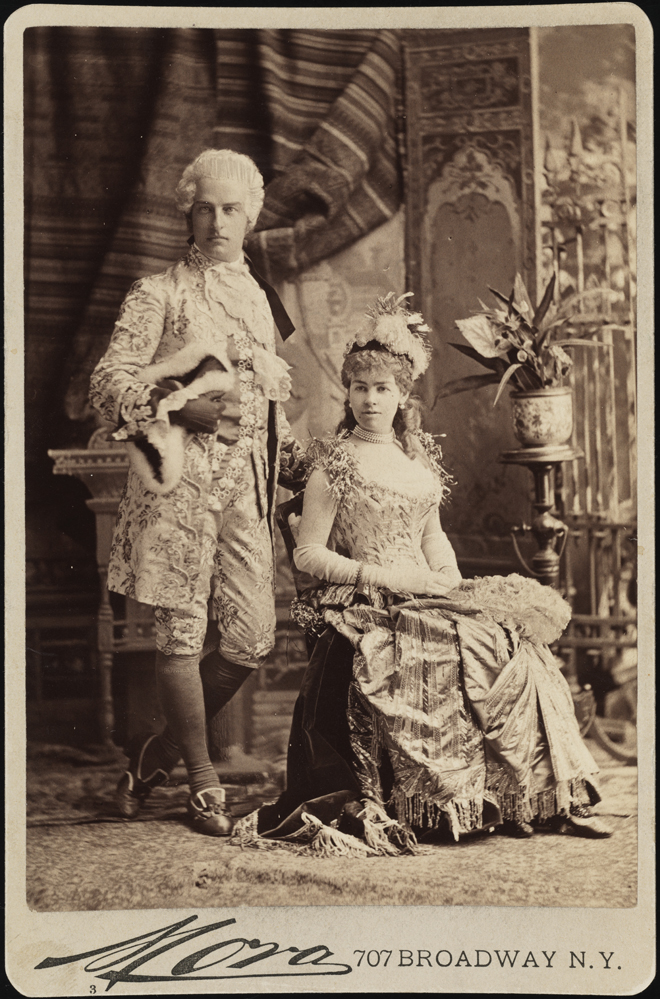

It is easy to see the casual display of over-the-top excess of the ball in these portraits of attendees in their costumes taken by Mora.

Miss Edith Fish was dressed as the Duchess of Burgundy, with real sapphires, rubies and emeralds studding the front of the dress.

Mora (b.1849). Miss Edith Fish (later Hon. Mrs. Oliver Northcote). 1883. Museum of the City of New York. 41.132.45.

Mora (b. 1849). Mr. and Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt II (neé Alice Claypoole Gwynne. 1883. Museum of the City of New York. F2012.58.1341.

One of the most amazing costumes was Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt II ‘s representation of “Electric Light” which even had a torch that lit up, thanks to batteries hidden in her dress. The dress is actually in the Museum’s costume collection and you can see it as it looked on Mrs. Cornelius Vanderbilt II in the cabinet card below, and how stunning it is in the full color collection image. (To take a closer look at the dress, visit our Worth/Mainbocher online exhibition here.)

Charles Frederick Worth House of Worth (Firm) Jean-Phillippe Worth (1856-1926). Fancy dress ensemble, “Electric Ligworn by Mrs. Cornelius Vht,” anderbilt at the 1883 Vanderbilt Ball. 1883. Museum of the City of New York. 51.284.3A-H

Dancers in the Dresden Quadrille wore all-white court costumes evoking the time of Frederick the Great and giving them the eerie and intentional look of living porcelain dolls.

For the Opera Bouffe quadrille, the costumes were just as elaborate. The New York Times described a dress as, “Miss Bessie Webb appeared as Mme. Le Diable in a red satin dress with a black velvet demon embroidered on it and the entire dress trimmed with demon fringe-that is to say, with a fringe ornamented with the heads and horns of little demons.” It’s not everyday that you hear the term “demon fringe”.

Speaking of things that you don’t hear or see on a daily basis, Miss Kate Fearing Strong wore a peculiar cat costume. Miss Strong, who Henry James described as “youthful and precocious,” went as her nickname “Puss”. Somewhat disturbingly, the entire costume consisted of a taxidermied cat head as seen in the image, but also seven cat tails sewn onto her skirt. Continuing with the animal theme, Alva’s sister-in-law went as a hornet, with an imported headdress made of diamonds.

After the last quadrille ended, the ball really began. Dozens of Louis XVIs, a King Lear “in his right mind”, Joan of Arc, Venetian noblewomen and hundreds of other costumed figures danced and drank among the flower filled house, including the third floor gymnasium that had been converted into a forest filled with palm trees and draped with bougainvillaeas and orchids. Dinner was served at 2 in the morning by the chefs of Delmonico’s working with the Vanderbilt’s small army of servants. The dancing continued until the sun was rising, diamonds and other jewels glinting in the changing light. Alva led her guests in one final Virginia reel and just like that, the ball was over. The fantasy world that Alva created turned back into reality as men in powdered wigs stumbled down Fifth Avenue, much to the amusement of children on their way to school.

Most contemporary sources put the cost of the ball at $250,000 (nearly 6 million dollars in today’s money), including such costs as $65,000 for champagne and $11,000 for flowers. It was conspicuous consumption at its finest and it worked. Newspapers across the country reported the most minute details and extolled Alva’s tastes and classiness. (This is not to say that there wasn’t a backlash to the ball. The New York Sun published this very stern article, critiquing the excess when there was so much suffering in the same city.). But as of March 27, 1883 the Vanderbilts were at the top of a new New York society that was not just limited to 400 people

100 Million Seeds From Native Plants Are Released Into the Brazilian Amazon by Daring Skydiver

Meet Lilli, the High-end German Call Girl Who Became Barbie

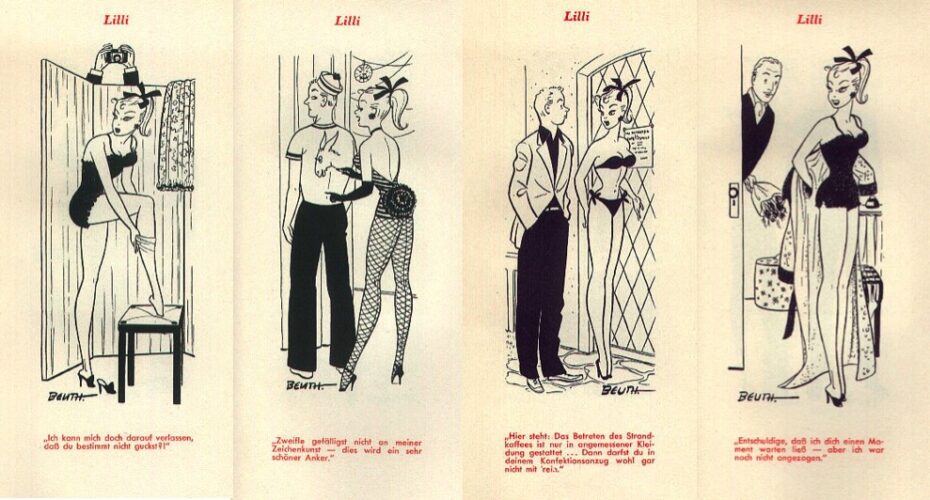

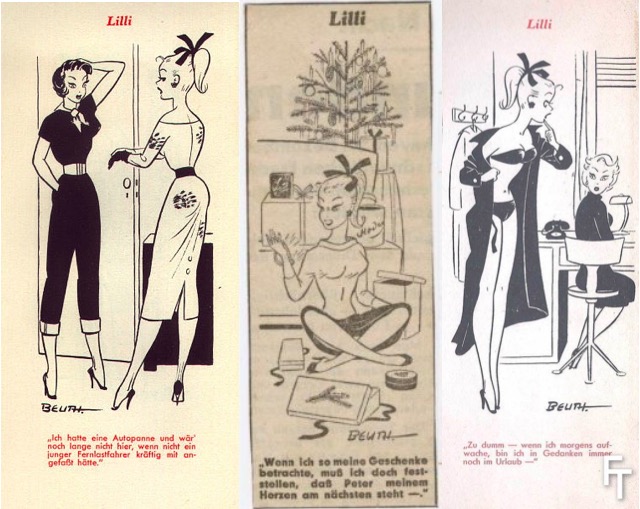

So it turns out Barbie’s original design was based on a German adult gag-gift escort doll named Lilli. That’s right, she wasn’t a dentist or a surgeon, an Olympian gymnast, a pet stylist or an ambassador for world peace. And she certainly wasn’t a toy for little girls…

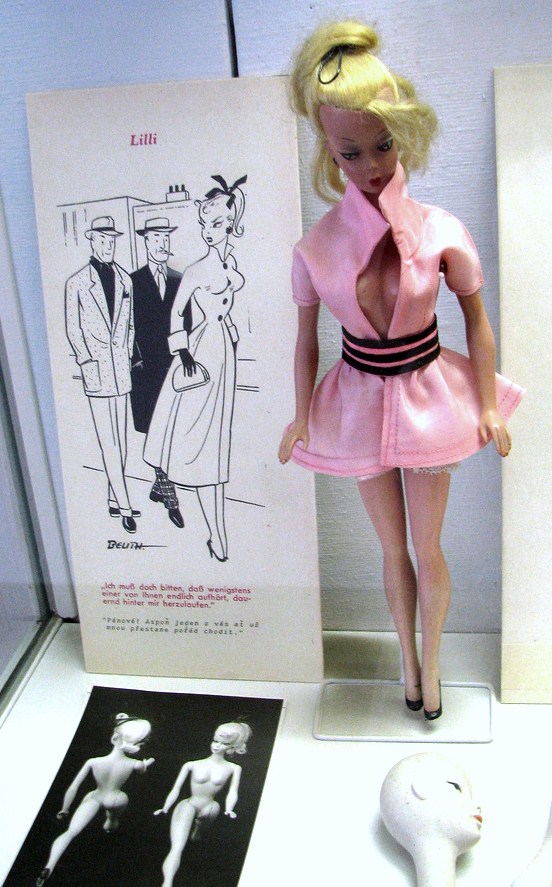

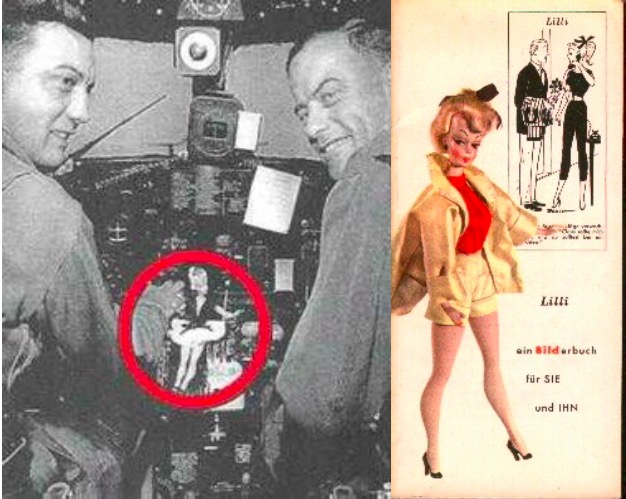

Lilli on display at the Barbie Museum in Prague

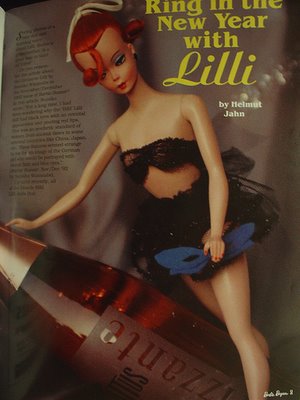

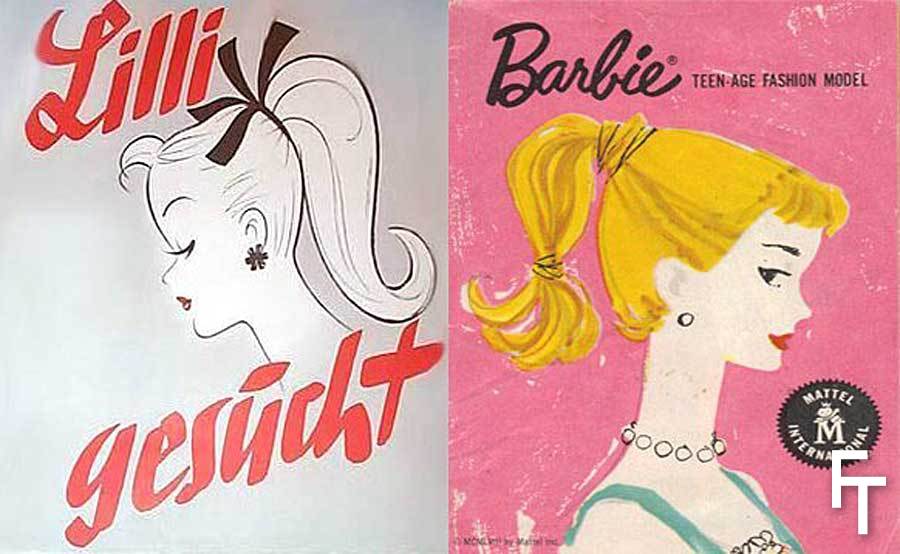

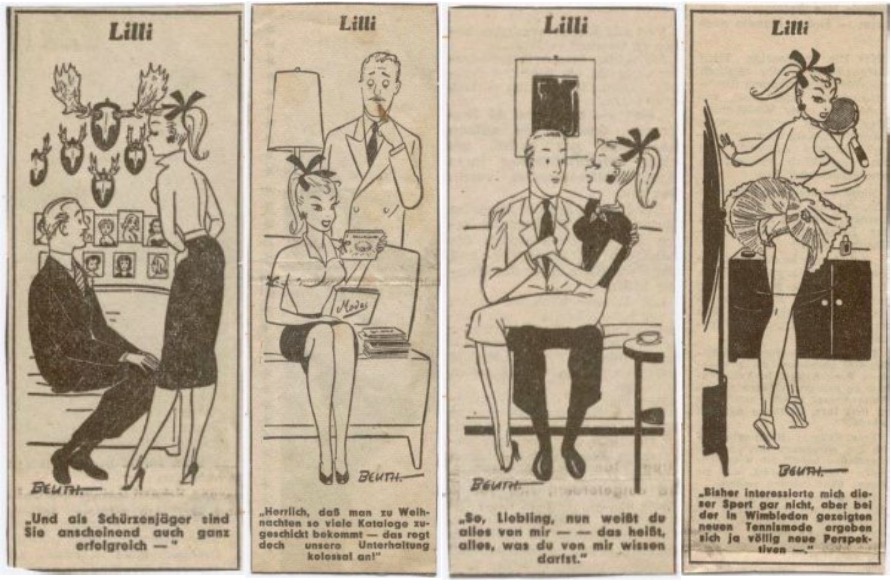

Unbeknownst to most, Barbie actually started out life in the late 1940s as a German cartoon character created by artist Reinhard Beuthien for the Hamburg-based tabloid, Bild-Zeitung. The comic strip character was known as “Bild Lilli”, a post-war gold-digging buxom broad who got by in life seducing wealthy male suitors.

She was famously quick-witted and known to talk back when it came to male authority. In one cartoon, Lilli is warned by a policeman for illegally wearing a bikini out on the sidewalk. Lilli responds, “Oh, and in your opinion, what part should I take off?”

She became so popular that in 1953, the newspaper decided to market a three-dimensional version which was sold as an adult novelty toy, available to buy from bars, tobacco kiosks and adult toy stores. They were often given out as bachelor party gag gifts and dangled from a car’s rearview mirror.

Fondation Tanagra

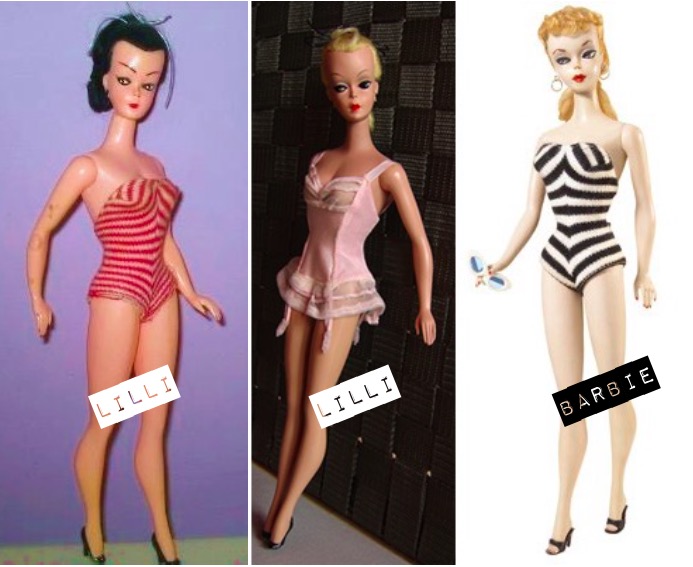

In the 1950s, one of the founders of Mattel, Ruth Handler (pictured above), was travelling to Europe and bought a few Lilli dolls to take home. She re-worked the design of the doll and later debuted Barbie at the New York toy fair on March 9, 1959.

Mattel acquired the rights to Bild Lilli in 1964, and production of the German doll ceased. (Funny how Barbie’s lighter skin tone was just about the only noticeable change in the early days).

Fondation Tanangara

And the rest is a history you’re a little more familiar with, and no doubt one Mattel is a little more comfortable with…

So which version would you prefer? Barbie’s ballsy European precursor or Mattel’s squeaky clean lookalike?

Discover more fascinating history about Bild Lilli and Barbie’s history written by a former designer at Mattel.

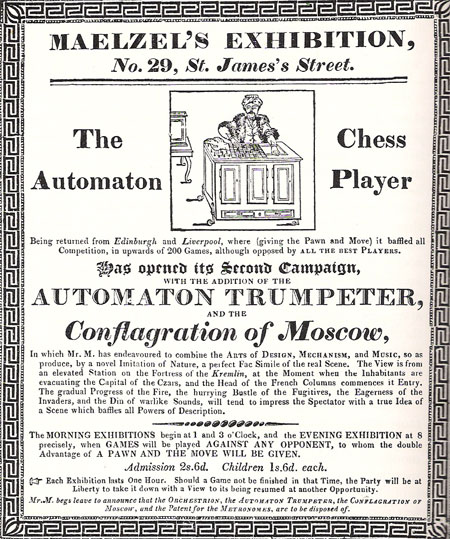

How a Mechanical Chess-Playing Turk gave Birth to the AI Debate 250 Years Ago

As we traverse the world of modern digital technology from smart phones to artificial intelligence, the game of chess still captivates and challenges people the world over. Chess, it seems, has thrived due to the advancement in connectivity. But 200 years earlier, before this electronic wizardry, there was an automated, mechanical marvel that would transfix the world with its chess-playing prowess. ‘The Turk’, as it would be known, travelled the world for over 80 years, defeating, delighting and mystifying the masses with its spectral talent. The Mechanical Turk quickly became a symbol of technological innovation and sparked the same heated debates we’re having right now about the nature of artificial intelligence, the limits of human ingenuity, and the possibility of constructing a machine capable of replicating human thought. However, behind the Turk’s enigmatic facade lay a secret that would only be revealed decades later, by none other than the master of mystery himself, Edgar Allan Poe. Let’s dive into the unbelievable tale of a remarkable mechanical creation that continues to intrigue to this day…

Wolfgang von Kempelen was a Hungarian Civil servant, author, inventor, and devotee of Empress Maria Theresa of Austria. In 1769, he attended a royal performance at Schönbrunn Palace by Francois Pelletier, the French illusionist who performed a unique act involving the use of magnets to bewilder and entrance the audience. The court and the Empress were aghast by the spectacle. Von Kempelen was not. The attention of the monarch had been shifted to this encroaching conjuror. Not to be outdone, Von kempelen threw down the gauntlet and decided that he would return with a creation that would surpass even Pelletier’s performance.

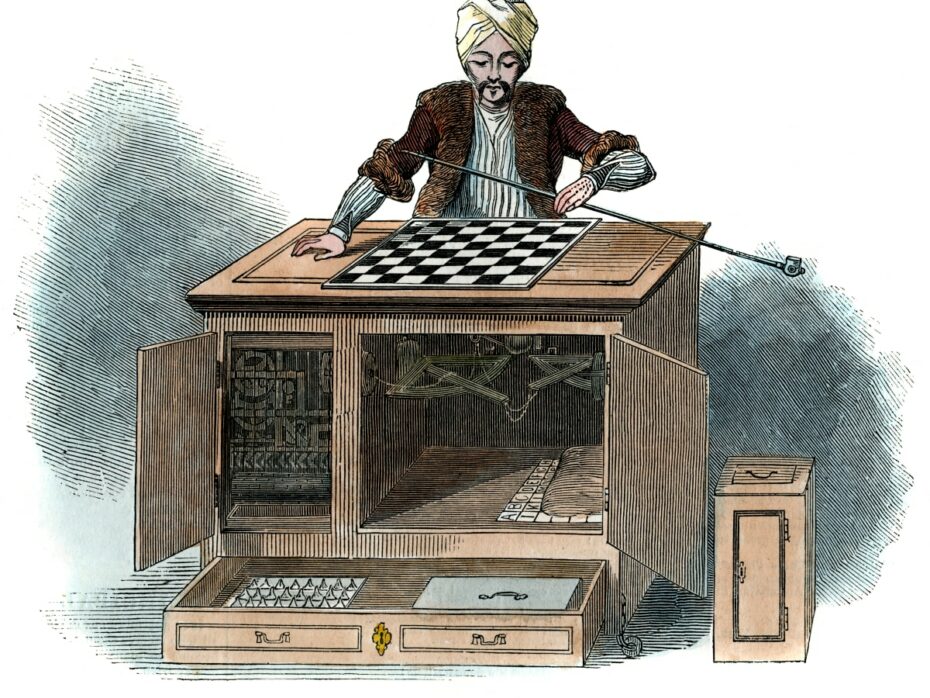

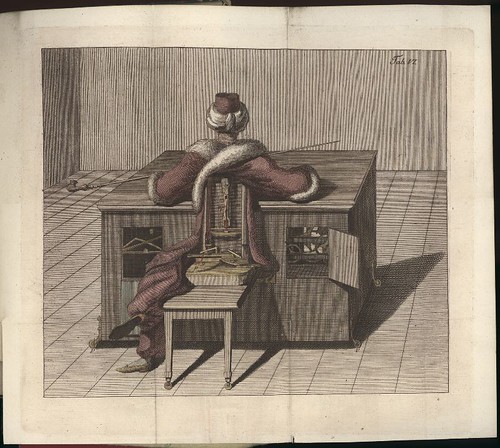

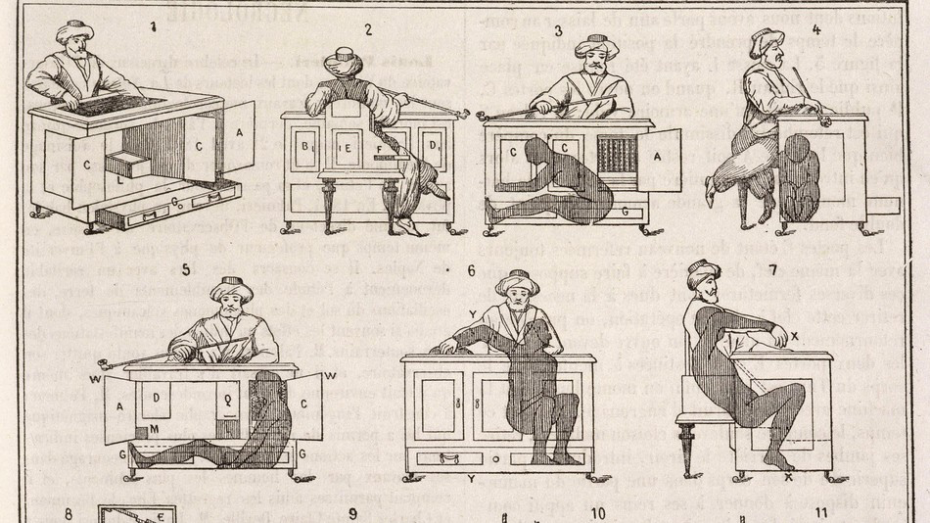

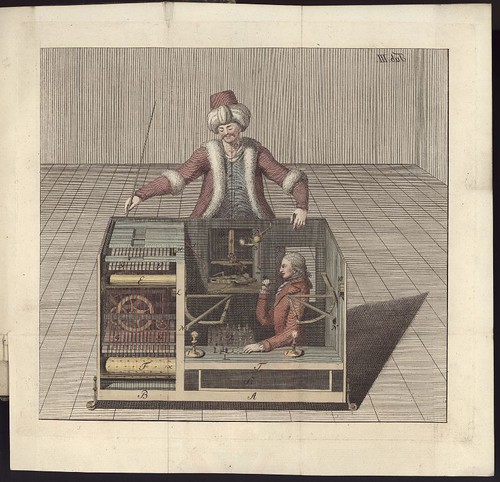

Von Kempelen retreated to his workshop, closed the doors and toiled away for 6 months, until finally, in 1770, he was ready to reveal his creation. What was unveiled perplexed the court; a motionless figure sitting at a large wooden cabinet overlooking a chessboard. The prone figure had the look of an Ottoman sorcerer; turban, and robes, even a long pipe, which he rested on a cushion. Von Kempelen declared his invention ‘The Turk’, an automaton Chess Player. He then proceeded to give the audience a tour of the machine, which included opening the cabinet to show the innards of the automaton and a demonstration of how it worked. A challenger was requested from the dignitaries at court and Count Ludwig von Cobenzl, a politician and keen chess player volunteered. Von Cobenzl was defeated by the automaton in under 30 minutes, and so was the next opponent and the next. The crowd was dumbfounded, this mechanical mystic seemed to be a master chess player. ‘The Turk’ performed his moves with his right hand, holding the pipe in his left. He would nod his head, three times if the king was in check, and twice if the queen was threatened. If his opponent tried to make an illegal move, ‘The Turk’, not to be fooled, would seemingly study the board and then move his opponent’s pieces back to the original spot. For its next trick, the curious contraption performed the Knights tour, a chess puzzle that requires the knight to occupy each square once on the board. The Court was amazed and more importantly for Von kempelen, so was the Empress.

The Turk was a hit and Von Kempelen was inundated with offers to display and tour his mechanical chess sorcerer. But for reasons that would later become apparent, Von Kempelen was hesitant to comply, and went as far as making excuses for the next decade as to why he couldn’t possibly exhibit his wondrous machine. Finally, Emperor Joseph II ordered Von Kempelen to Vienna to display the Turk and play the Grand Duke Paul of Russia. The appearance was such a hit that he was dispatched to Europe to great fanfare and success. In 1873, the tour began in France where Von Kempelen displayed his machine to crowds of people wanting to catch a glimpse of the mysterious mechanical chess master. The Turk even played Benjamin Franklin, then the ambassador to France. When the tour hit Paris, the automaton played one of the best chess players of the era, André Danican Philidor. It lost the match but Philidor said later “It was his most fatiguing game of chess ever!”

The tour of Europe continued, staying in London for a year, before bamboozling audiences in Dresden, Amsterdam and Potsdam. With fame though, came the doubters. The sceptics just could not believe a man could make a machine of such guile and skill. Articles and books were written with wild theories trying to expose Van Kempelen. When Von Kempelen died at the age of 70, it looked like the secrets of his invention would die with him. Until the musician, Johann Nepomuk Mälzel, purchased the Turk from Von Kemeplen’s son and the whole spectacle came to the public’s attention again. In 1809, the Turk would play maybe its most prestigious and unpredictable opponent, the self-proclaimed Emperor of France, Napoleon Bonaparte. The match was set at Schönbrunn Palace and Bonaparte, in an attempt to take the advantage, decided to play white. He then made three illegal moves, presumably to try and trick The Turk. Undeterred, the machine replaced the pieces in the original spot and continued, on the 3rd time, The Turk swept all the pieces off the board with his arm in a seemingly mechanised tantrum. Amused, Napoleon started the game a fresh, confident in his savoir-faire and chess prowess. He lost in 19 moves. The emperor seemed to take it well, more bemused than annoyed. Mälzel must have breathed a sigh of relief, because if Napoleon had found out that a man of even smaller stature than himself was hiding inside the machine all along, the musician may have lost his head.

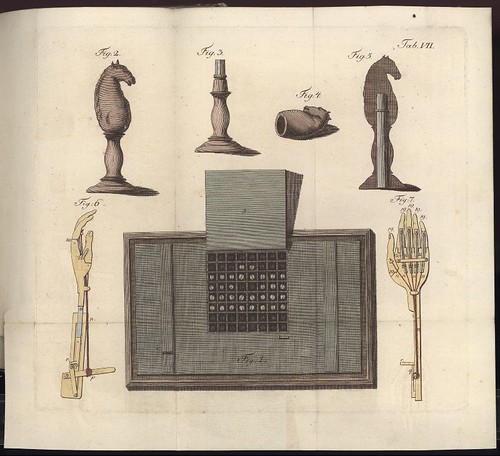

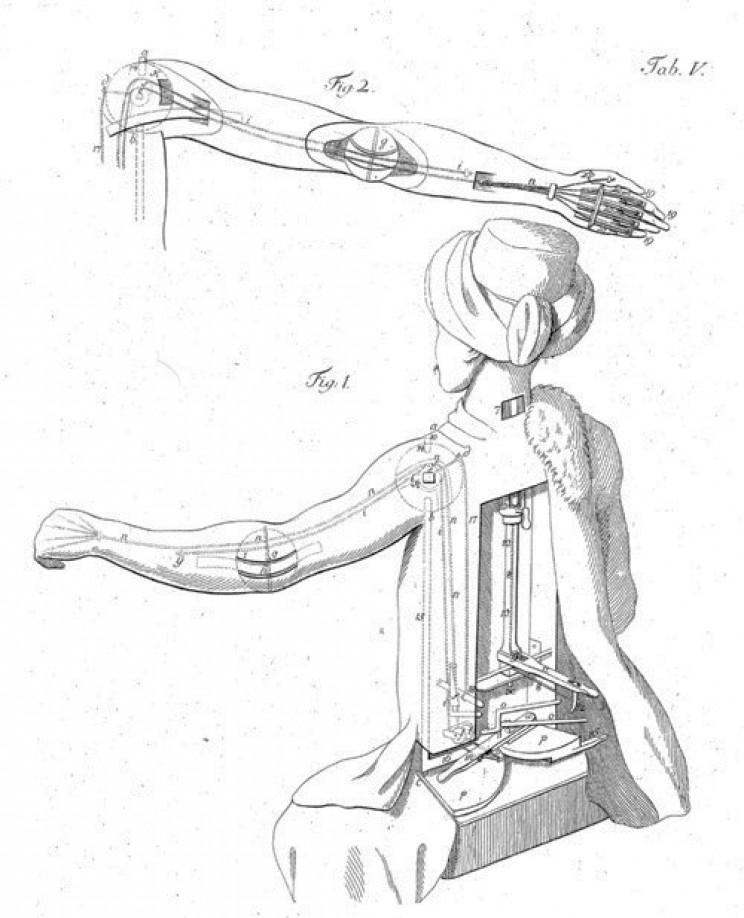

The ruse had begun with Von Kempelen, having seen the illusionist at the palace in Vienna. He had understood that the deception lay in the misdirection of his audience. He’d constructed the box so that an operator could hide inside and play the machine’s moves for it. The controller would have to be small enough to hide and a good enough chess player to beat most opponents. This must have been why Von Kempelen was so reticent in touring with his contraption; the availability of willing and miniature master chess players clearly presented a problem. How the trick worked is similar to the magician’s commonly seen box illusion. When the doors were opened, allowing the audience to inspect the insides, the operator would slide to different compartments on a moveable seat, which moved machinery into position. The cogs and gears were all for show and didn’t operate anything. The controller witnessed the game through magnets attached to the bottom of the pieces. A pegboard was used to keep track of the game and a system of pantographic levers were used to control ‘The Turks’ arm and hand to play his moves. On the outside, there had been fitted a revolving numbered disk so the operator could communicate in code, and a ventilation system so the smoke from a candle inside appeared to be dispersed through the Turks turban perhaps to replicate steam. Mälzel would also add a voice box to The Turk to say Échec, French for check, to add to its eerie quality.

The original hidden chess master who played for Von Kempelen remains unknown, but when Mälzel bought The Turk, he had procured the assistance of Johann Baptist Allgaier an Austrian-German player who would pose as Mälzel’s private secretary on the tour. Other chess masters who would become involved include, Aaron Alexandre, William Lewis, Jacques Mouret, and William Schlumberger. In 1826, Mälzel and ‘The Turk’ would tour North America with Schlumberger at the controls; on this tour Edgar Allan Poe was witness to the event and would go on to write his essay an exposé of Mälzel’s chess player. Poe had studied the machine and claimed the pattern and emotive type of play could only be down to a sentient being. Either this, or he’d heard about the two boys in Boston who had seen Schlumberger sneaking out of the back of the cabinet. In America, Schlumberger would succumb to yellow fever, and then Mälzel would die on the return trip.

Interest in The Turk would eventually wain and it would pass through several hands before succumbing to a mysterious fire in a Chinese Museum. Von Kemeplen had constructed a machine when a fear of mysticism and magic would give way to the Industrial Revolution. The Turk though an automated hoax, would allow a peak behind the curtain of an eventual future when automation and artificial intelligence would emerge. In 1997, Deep Blue IBM’s supercomputer challenged and beat grandmaster Gary Kasparov. This would be the first time a machine would beat a current world champion without human assistance. Or did it?!

Words by Liam Ward

'Ghosts' of the Coal Mines

These horses or "pit ponies" were deprived of experiencing the sunlight and fresh air. Instead, they lived in darkness underground, relying on their instincts and the guidance of their human partners, known as conogons.

These horses were born, worked, and perished in the dark, enduring strenuous labor. It was not uncommon for a single horse to pull up to eight heavy coal wagons alone. Despite their challenging circumstances, these animals maintained their dignity and were aware of their rights, such as refusing to move if they felt burdened with excessive wagons. They also possessed a remarkable sense of time, knowing when their working day should end and finding their way back to the stables even in darkness. This demanding work of horses in the mines continued until 1972 when technology took over, marking the end of an era.

On December 3, 1972, Ruby, the last miner's horse, emerged from the mines in a grand fashion. Accompanied by an orchestra, Ruby, adorned with a flower wreath, was brought out of the darkness, symbolizing the conclusion of the era of mining horses and their connogon partners. To commemorate their shared labor underground, a sculptural composition named "Conogon" was erected within the Museum-Reserve "Red Hill".

Terracotta Warriors

Photographed in 1974, freshly excavated 2000 year old Terracotta warriors still showing the original color scheme before rapid deterioration. Rt Historical Artefacts

Rare Spotless Giraffe

A rare spotless giraffe born at Brights Zoo in Limestone, Tennessee, this summer captured hearts. Now, the newborn finally has a name. After asking the public to vote on a name for the baby, the zoo on Tuesday declared the winner. The giraffe will be called Kipekee, which means "unique" in Swahili.

The zoo announced the choice on Facebook, where, in a post last month, it asked people to choose between four symbolic names: Kipekee, which means "unique;" Firyali, which means "unusual" or "extraordinary;" Shakiri, which means "she is most beautiful" and Jamella, which means "one of great beauty."

The zoo received over 40,000 votes, and Kipekee won by a margin of 6,000 votes.

The Hasanlu Lovers

The 2,800-year-old Hasanlu Lovers were found in a bin in Iran. The two skeletons buried in ground appear to kiss each other. Other than the gender dispute, historians are not sure why they came to be in the bin - perhaps they were hiding during the final sacking of Hasanlu.

'A Helping Hand from the Media'

This might be one of the most famous images in photographic history.

.png)