How did the Heart Become the Symbol of Love?

Once upon a time, a knight was really pissed off. He had just discovered that his wife took a lover, and naturally, sought revenge in a joust to the death with his rival. But even that victory wasn’t enough to quench his rage, so he cut out the heart of his wife’s lover and gave it to his personal chef with specific instructions: cook this into a ragout for my wife. Sure enough, that night she licked her plate clean. And so goes a ye olde legend that is both Patrick Bateman-level crazy, and reaffirms how deeply rooted the heart’s role is as a powerful – and dangerous – symbol of love. But how did it get to the V-Day greeting card aisle, all the way from the era of chivalry – and what did it symbolise before that? When did the heart beat for love?

Anonymous, British or American, 19th century. ©The Metropolitan Museum

The earliest heart shaped symbol might have actually represented the seed pod of the silphium plant, which was used as contraception in ancient Libya. It also might also have simply represented the shape of someone’s backside or even a woman’s vulva. The ancient origins are manifold, and pretty much left to historical speculation.

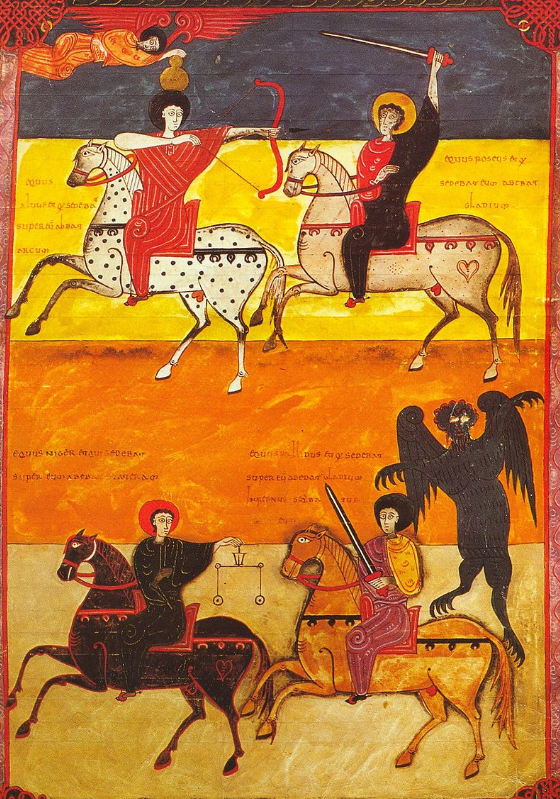

How else “did the heart icon exist before the high Middle Ages?” asks author Marilyn Yalom in The Amorous Heart: An Unconventional History of Love. A heart shaped symbol was found on Mediterranean coins in the 6th century BCE, as well as on chalices – which means it might’ve been associated with the heart shaped leaves of vines. Meanwhile, in a 14th century Spanish depiction of the Four Horsemen of the Apocalypse, we also see hearts – the right side up – on some of the steeds’ rear ends:

“[The heart] might’ve also been the brand for horses,” says Yalom, “Why not? The double lobes do suggest haunches.” Were they symbols of war? Strength? All the wine they would drink after battle? Who knows. But in the Middle Ages, the real fun begins. This was the age of courtly love. Medieval philosophers looked to Aristotle, who said that sentiment lived not in the brain but the heart, for cues on where to pinpoint thine #feels. In Medieval Bodies: Life, Death and Art in the Middle Ages, Josh Hartnell explains that they also inherited the Greek idea that the heart was the first organ your body made, and hence, the one that most anchored your human existence – it was the “house of the human soul.”

But one of the biggest myths of the medieval heart is that it always had the scalloped shape we’re used to. At first, hearts were depicted like wonky pears, pine cones, or rhombuses, which is partially because back in the ye olde times, it was still pretty blasphemous to dissect the sacred human body. We knew that the heart pumped out blood, but not that all that blood returned on a superhighway of veins and arteries. Which is why it started to get such a track record for being susceptible to emotions – the “bleeding heart,” as it were.

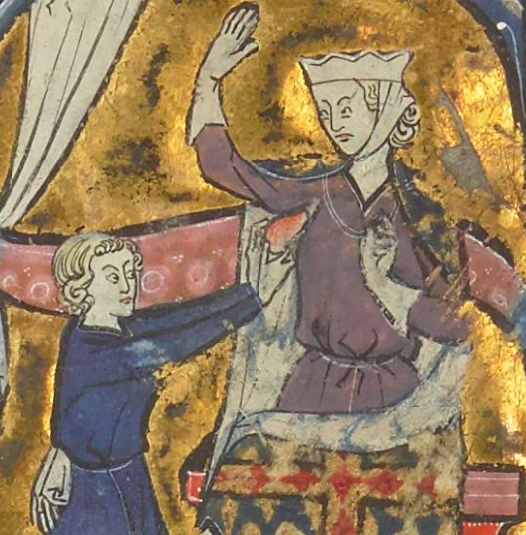

Until the 14th century, hearts were usually depicted upside down. The first depiction of a heart in romantic context is believed to be in this 13th century French manuscript “Roman de la Poire” or Romance of the Pear – proving that, yes folks, the French have always been obsessed with love – and you’ll notice the heart is indeed upside down, looking a bit like a mango.

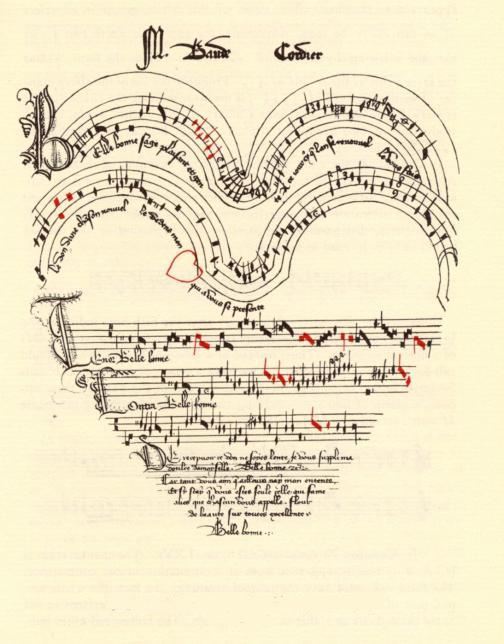

The heart, as either a lumpy fruit shape or its famous scalloped form, became a motif of troubadour poems, marble coffins, and sheet music; it was seen on playing cards, in manuscript doodles, and fashion too – like the “Escoffin,” a kind of heart shaped head gear…

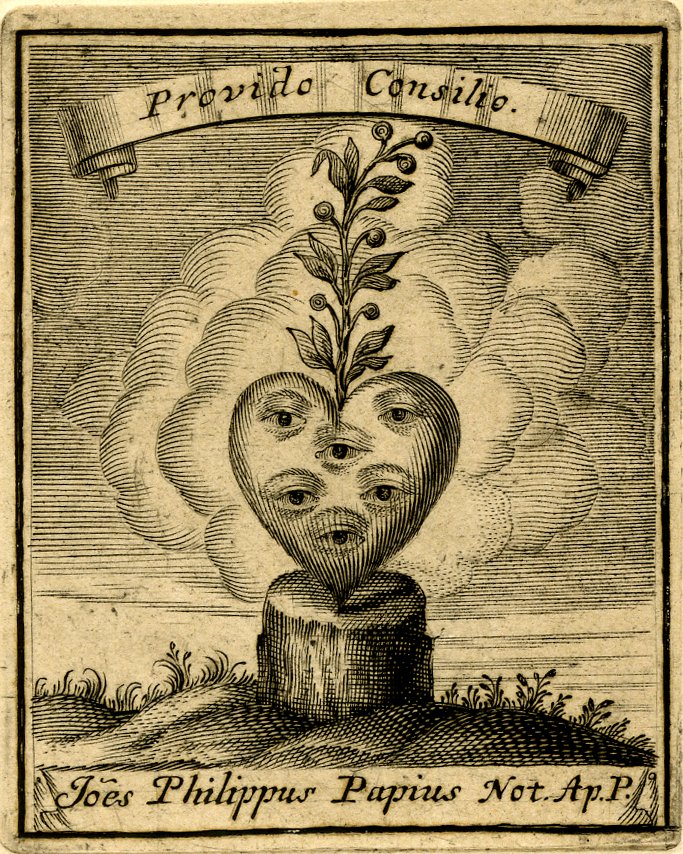

Lest we forget, this was an era that took its dragons and even weirder medieval monsters very seriously, so the heart was susceptible to some very strange foul play (see: aforementioned heart ragout story). Folks in the middle ages very much believed the “you are what you eat” mantra, and so feasting on a sinful heart was a veritable death sentence. The heart, being the all-absorbant organ that it was, had eyes of its own.

This brings us to the origins of Valentine’s Day. Once upon a time, “courtly love” was a literary obsession with a specific romantic narrative: respectful knight pursues chaste maiden, usually with the help of a troubadour and a lyre. Dragons optional. Lather, rinse, repeat. But the heart also spoke to divine love, from Christianity to Islam, and it’s in straddling these two metaphors that V-Day is born.

Rumour has it the 14th century English author Geoffrey Chaucer (The Canterbury Tales) was quite taken with the story of a martyred Christian from Roman times, Valentine, who married couples in secret. That’s right, there really was a flesh-and-blood Italian behind the kitsch holiday we’ve got today – and you can visit his remains here. There’s still a lot we don’t know about Mr. Valentine, but the gist of his story made for perfect holiday fodder.

via Messy Messy