This cat door is considered the oldest on record. Installed in 1598, the cat door allowed cats to enter and hunt mice and rats, which were drawn to the lubricated animal fat applied to the mechanics of a large astronomical clock.

Tobe Roberts, Senior Associate Manager at Atchity Productions Joins Kevin Smith's Birthday Bash!

Tobe Roberts joins Kevin Smith's 55th Birthday Bash at his comic book store, Jay and Silent Bob's Secret Stash in Red Bank, New Jersey.

A comic book writer, author, comedian/raconteur, and internet radio personality, he is best known for his films "Clerks" (1994), "Jay and Silent Bob Strike Back" (2001), and "Clerks II" (2006) and his character Silent Bob. "Clerks: The Animated Series" (an adult sitcom) aired for a short time on ABC-TV starting in May 2000. (In 2019, "Clerks" was selected by the Library of Congress for preservation in the United States National Film Registry for being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant.")

Ancient Stone Cutting

In Japan, ancient quarry sites still preserve fascinating traces of how people once cut and shaped massive stones. At many of these sites, you’ll notice neat rows of small square holes carved into the rock—these are wedge sockets, the result of a technique where workers drove wooden or metal wedges into the stone to split it along a straight line. It was a smart and straightforward method that let them carefully control the break and create smooth, uniform blocks.

There’s also evidence that an even older method might have been used. In this technique, dry wooden wedges were inserted into cracks, then soaked with water. As the wood expanded, it slowly forced the rock apart. This approach was also seen in ancient Egypt and other civilizations.

What’s especially intriguing is that Japan has many of these prehistoric stone-working sites, even though its written history only dates back about 1,600 years. This points to a much older and largely unknown tradition of stone craftsmanship. Some of the remaining stone foundations suggest that impressive structures once stood there—now lost to time, earthquakes, or both

Man 'O War

Man o' War was an American Thoroughbred racehorse widely considered one of the greatest of all time. Born in 1917 at the Nursery Stud in Kentucky, he was sired by Fair Play and out of Mahubah. His early years were marked by natural talent, and it quickly became clear that he was special.

Man o' War's racing career was spectacular. He raced from 1919 to 1920, winning 20 of his 21 races. His only loss came in a race against a horse named Upset, which was considered an unexpected defeat due to Man o' War's dominance up until that point. Despite this loss, Man o' War's achievements were unparalleled.

He won numerous prestigious races, including the Belmont Stakes, where he won by an astounding 20 lengths, and the Preakness Stakes, among others. Man o' War's dominance on the racetrack was not only measured by the number of races he won but also by the way he won them—often in commanding fashion that left fans and critics in awe.

After retiring from racing at the age of three, Man o' War became a successful sire. He produced many notable offspring, including the famous War Admiral, another Triple Crown winner. Man o' War's legacy as a racehorse and a sire has left a lasting impact on the world of horse racing.

Man o' War was retired to stud in 1921 and lived until 1947. Today, he is remembered not only for his speed and victories but also for his lasting influence on the sport of horse racing. His legacy continues to be celebrated as one of the greatest in the history of the sport.

The “Race of the Century""

On Tuesday 1 November 1938, the two racehorses finally met in what was euphorically dubbed the “Race of the Century”. The race, which was to be run over a mile and 3/16, still ranks as one of the greatest sporting events in US history.

Although it was a weekday, an unusually large crowd of 40,000 gathered at the track for the time. So many people wanted to witness this racing event that they even had to open the infield to spectators. Trains had brought spectators from all over the country to the Pimlico Racecourse near Baltimore, Maryland and 40 million people followed the race on the radio. War Admiral was the undisputed favorite for the race; the betting odds at most bookmakers were 1 to 4 in his favor and most sports journalists were also unanimous about the outcome of this race.

When the starting bell rang on 1 November, Seabiscuit took off with such speed that he was already a length ahead of War Admiral after 20 seconds. Seabiscuit was able to maintain this gap for most of the race, but on the back straight War Admiral began to close the gap and draw level with Seabiscuit. George Woolf did not spur Seabiscuit on immediately, but first allowed Seabiscuit to perceive the opposing horse beside him. When he then released the reins, Seabiscuit still had enough power to increase his racing speed once more. War Admiral could not keep up; when Seabiscuit crossed the finish line, he was four lengths ahead of his opponent. On 10 April 1940, it was officially announced that Seabiscuit would run no more races. He returned to Howard’s Ridgewood Ranch .

He left the Turf as the most successful racehorse of his time.

Andrew Irvine and George Mallory

A century after mountaineer Andrew Irvine vanished alongside George Mallory, a National Geographic team may have uncovered vital clues to one of the greatest unsolved mysteries in the history of exploration.

Irvine and Mallory were last seen on June 8, 1924, during their daring attempt to become the first people to summit Mount Everest.

Mallory's body was discovered in 1999, but the discovery didn't definitively answer whether he and Irvine reached the summit.

In 2024, National Geographic reported that a team led by Jimmy Chin found Irvine's partial remains on the Central Rongbuk Glacier.

The discovery of both Mallory and Irvine's remains has provided some clues, but the debate continues about whether they reached the summit before their deaths.

Irvine reportedly carried a camera, and the possibility of finding it (and its film) continues to fuel speculation about their ascent.

Whether they reached the top before disappearing has remained an enduring mystery. If they had succeeded, their achievement would have predated Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s historic 1953 ascent by 29 years.

Photo Credits: (Jimmy Chin/AP/Mount Everest Foundation/Royal Geographical Society via Getty Images)

Medieval tale of Merlin and King Arthur found hiding as a book cover

|

Former Cambridge archivist Sian Collins first spotted the manuscript fragment in 2019 while recataloging estate records from Huntingfield Manor, owned by the Vanneck family of Heveningham, in Suffolk, England. Serving as the cover for an archival property record, the pages previously had been recorded as a 14th century story of Sir Gawain.

But Collins, now the head of special collections and archives at the University of Wales Trinity Saint David, noticed that the text was written in Old French, the language used by aristocracy and England’s royal court after the Norman Conquest in 1066. She also saw names like Gawain and Excalibur within the text.

Collins and the other researchers were able to decipher text describing the fight and ultimate victory of Gawain, his brothers and his father King Loth versus the Saxon Kings Dodalis, Moydas, Oriancés, and Brandalus. The other page shared a scene from King Arthur’s court in which Merlin appears disguised as a dashing harpist, according to a translation provided by the researchers.

Tracing the book’s journey

The pages had been torn, folded and sewn, making it impossible to decipher the text or determine when it was written. A team of Cambridge experts came together to conduct a detailed set of analyses.

After analyzing the pages, the researchers believe the manuscript, bearing telltale decorative initials in red and blue, was written between 1275 and 1315 in northern France, then later imported to England.

They think it was a short version of the “Suite Vulgate du Merlin.” Because each copy was individually written by hand by medieval scribes, a process that could take months, there are distinguishing typos, such as “Dorilas” instead of “Dodalis” for one of the Saxon kings’ names.

“Each medieval copy of a text is unique: it presents lots of variations because the written language was much more fluid and less codified than nowadays,” Fabry-Tehranchi said. “Grammatical and spelling rules were established much later.”

But it was common to discard and repurpose old medieval manuscripts by the end of the 16th century as printing became popular and the true value of the pages became their sturdy parchment that could be used for covers, Fabry-Tehranchi said.

“It had probably become harder to decipher and understand Old French, and more up to date English versions of the Arthurian romances, such as (Sir Thomas) Malory’s ‘Morte D’Arthur’ were now available for readers in England,” Fabry-Tehranchi said.

The updated Arthurian texts were edited to be more modern and easier to read, said Dr. Laura Campbell, associate professor in the School of Modern Languages and Cultures at Durham University in Durham, England, and president of the British branch of The International Arthurian Society. Campbell was not involved in the project, but has previously worked on the discovery of another manuscript known as the Bristol Merlin.

“This suggests that the style and language of these 13th-century French stories were hitting a point where they badly needed an update to appeal to new generations of readers, and this purpose was being fulfilled by in print as opposed to in manuscript form,” Campbell said. “This is something that I think is really important about the Arthurian legend — it has such appeal and longevity because it’s a timeless story that’s open to being constantly updated and adapted to suit the tastes of its readers.” via CNN

Coworkers That Are Genuinely Walking Rays Of Sunshine

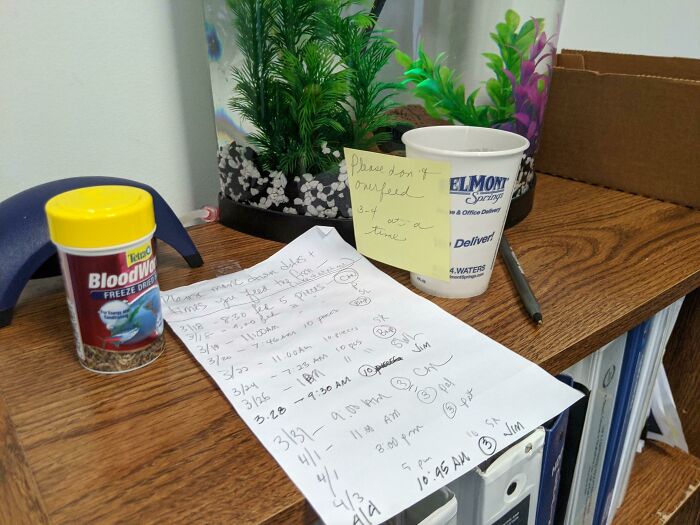

Office Fish

This person asked their coworkers to help feed their fish in the office while they were stuck working at home. Not only did one person volunteer, but it looks like the whole office signed up to help! His coworkers, to his delight and amazement, took this seriously and kept track of it in a logbook.

It’s impossible to overestimate the importance of working with intelligent people. The logbook isn’t just cute, but an important safety measure alongside the note on the cup reading, “Please don’t overfeed.” The fish’s owner must have appreciated the level of care their coworkers put into feeding the fish.

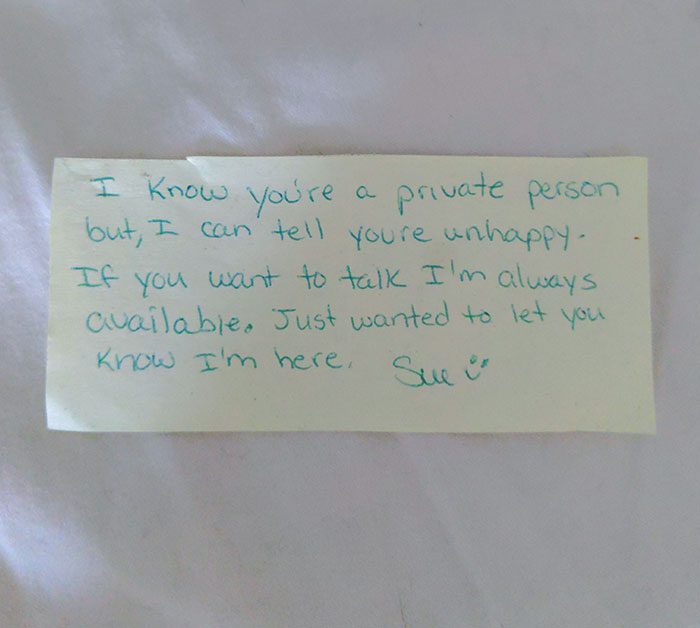

Something as simple as a sticky note can make all the difference to someone going through a rough time. The coworker that left this note must have a big heart to recognize when someone isn’t happy but still respects their personal space with a small yet grand gesture.

I’ve Got You Covered

It took us a minute to process this image. Why is a construction worker digging a wholesome gesture? Well, take a look at the umbrella over his head. And, look at how it’s held up. This kind gesture deserves to be recognized.

You might not understand the caption “I’m a nice colleague” if you haven’t properly understood the image. A coworker came up with a way to protect their colleague from the elements while they were digging. We can only assume that the job required only one of them to be laboring outside, for this little setup to occur.

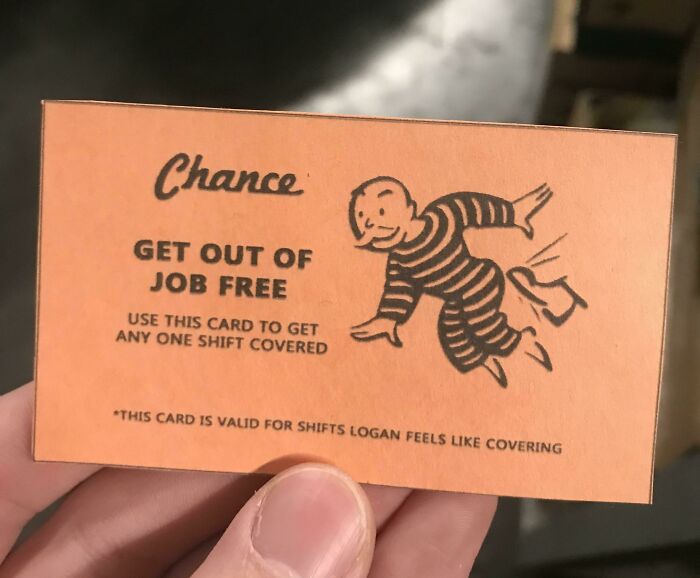

Birthday Work Pass

What could be a better birthday present than a free pass to get away from work whenever you want? Without thinking, we might choose this over a box of cupcakes However, we hope no one asks us to choose between the two, especially if the cupcakes are red velvet.

This is a fantastic concept for anyone who works in a shift-based environment. On your coworker’s birthday, you can give them an access card to use to get away from work. It’s crucial, though, that the receiver understands that the card is only good for the shift you’re willing to cover.

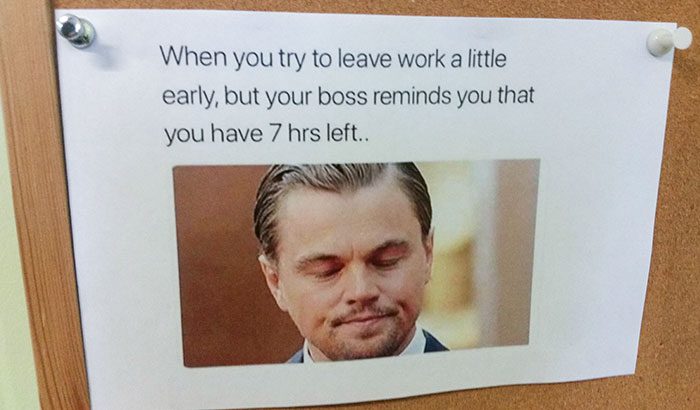

Memes From The Receptionist

This is by far the most amusing thing we’ve ever seen. This 66-year-old receptionist devotes their time and resources to making their coworkers happy. Even if work is chaotic, no one will be able to look at this and not grin. It reminds them that they are all in this together.

However, we’re curious as to what the employer thinks of this and other memes found on their receptionist’s desk. This is a fantastic way to get everyone in the office in a good attitude. We’ll always stroll past the receptionist’s desk just to chuckle if we work somewhere like this.