Source: The Guardian/Dan Kitwood, Getty Images

Throughout the day, interest in global

financial centers was intense, with opinions split on whether an English

exit was long overdue and smart; or rushing to judgment and foolish.

The latter attitude was prominent largely because 60 percent of British

EU export markets would still be close by for the UK, but possibly

off-limits. The UK might eventually have to go outside the borders of

the EU to replace lost customers there, if they cannot renegotiate the

trade agreements successfully.

As details of departure in

this first-time event materialize, its big-deal status becomes plain.

The EU in its modern configuration in 1957. Before that, versions of

the organizations proved only temporary. There is a feeling that more

than UK’s departure is at stake.

A vision by experts who have studied

Europe’s recovery from WW II indicates that long economic recovery is

over, and the EU and other countries are on their own to pick up the

slack now. Many statements from EU officials chide the UK for leaving,

and want to get the bitter goodbye over. In London, the referendum

outcome has caused a shake up in parliament already, starting with a new

Prime Minister.

Implications

of John Bull jumping ship have also registered a flashing “ten” on the

alarm bell in Brussels, where the European Union headquarters, as well

as in other financial centers worldwide. Furthermore, the Anglo choice

to exit has alerted Brussels and financial centers that other member

states could follow suit. Times are getting harder worldwide, even in

China’s miraculous evolution, as the rising tide of recovery from WW II

begins going back to sea, in a powerful ebb tide.

The

United Kingdom—comprised of England, Wales, Scotland and Ireland—was one

of the nine charter members of those early versions of the European

Union, beginning in the 1950s. This was over ten years after both WW II

winners and losers in Europe suffered the industrial shocks of waging

total warfare from 1941 to 1945. Economically, they were on their knees

postwar, although the American Marshall Plan launched in 1958, soon to

begin to impact recovery.

At the

outset of the post-war period, many nations across Europe were not

competitive, in nearly every economic sector, having been pulverized

from the air by waves of Allied bombers. On the ground, advancing tanks

and field artillery of the Allies bombarded from the West and Russia

from the East–closing the geographic vice—and leveling broad swaths of

territory and the means to fully exist, much less produce on a scale

for export markets. The Allies divided Germany into East Germany and

West Germany, neither a match for the mighty industrial engine of

Germany .

An

excerpt from an address given by Secretary of State George C. Marshall

during 1947 at Harvard University assessed Europe’s dire status then:

“The

truth of the matter is that Europe’s requirements for the next three or

four years of foreign food and other essential products—principally from

America—are so much greater than her present ability to pay that she

must have substantial additional help or face economic, social, and

political deterioration of a very grave character.”

That

speech became the official announcement of the Marshall Plan or the

European Recovery Act, its designation in Congress. The act directed $19

billion U.S. dollars into the recovery of Europe, from 1948 through

1951. To appreciate the magnitude of the American investment, the future

value of the 1948-51 investment of $19 billion at an assumed 5.5%

annual discount rate for 65 years expands to $673 billion in 2015.

However, Russia objected to America interfering in the internal affairs

of eastern European countries, and did not authorize its use in that

sector of Europe, which it controlled. Both Poland and Czechoslakia in

that sector wanted to register in the program, but were prevented to do

so by Russia’s objection.

This instant green gusher reinvigorated

a comatose Western Europe, and provided massive export

business for U.S. manufacturers. Its effect was to boost America, in a

way that topped any of the make-work stimulants of FDR’s New Deal, in

the late 1930s. Actually, it began the long-term upturn of the U.S.

economy post-WW II.

Within

Western Europe, the huge success of the Marshall Plan provided a

jumpstart for academic, industrial and political leaders to sell the

general idea of the European Union. Its idealism was to instill

cooperation among recovered European states in the association, in order

to smooth barriers to trading with each other and develop related

management sharing. In early years of its development, the goal was

principally an ending to the frequent costly wars in Europe, often over

ownership of natural resources—coal reserves especially—but it expanded its reach and depth of purpose as years passed by.

The

ultimate goal became a union of economic and political activities.

Today, the EU administers a sovereign currency (euro), central bank,

legislature, laws, courts, tariffs, taxes, immigration quotas, and a

myriad of administrative agencies and laws present in most any modern

state on the planet.

An

anatomy of United Kingdom voting in the Brexit referendum shows that

“withdraw” voters tended to be young and live in urban environments,

while “remain” balloting occurred mostly in rural areas. In the former,

young workers and professional people were concentrated , while the

latter residents resided in rural areas, on farms and in small towns.

The clash at the polls was mainly between them.

EU laws

dealing with setting quotas for foreign workers to find employment in

member states, were rumored to be a special problem in the UK. There are

also rules for allowing labor to enter from countries outside the EU.

In addition, the required eight percent of their workforce represented

by EU immigrants reportedly was a problem in London, especially among

young voters. Apparently, there was also a Brit reaction to EU banking

rules, and heavy paperwork demands by administrators and managers.

In predicting whether other members will

want to depart also, keep in mind that the UK has been unique as the

only offshore member state. A detached position made procedures and

trading to and from the continent for them more problematic.

There

were scads of EU regulation and administration for the UK to dislike. In

addition and although not publically discussed, troublesome from the UK

viewpoint surely was their anemic Gross Domestic Product (GDP), in

recent years.

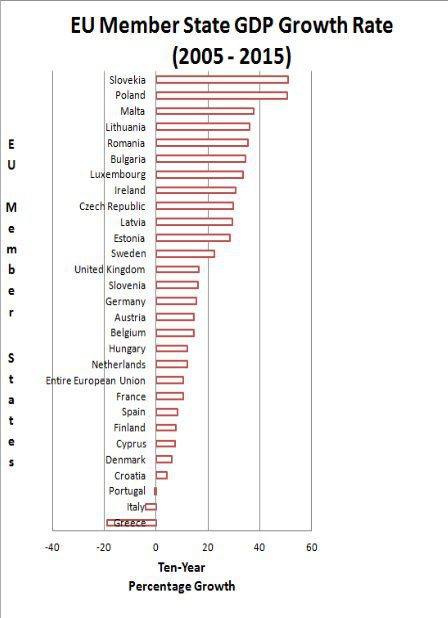

Its average annual rise in GDP from 2005

through 2015 was 1.4 percent, putting UK in 13th place in the EU.

Perhaps even more irritating, nine members of the current EU from

Eastern Europe are in the top ten of GDP growth, in spite of once being

ruled by a failed communism in Eastern Europe in 1991. The UK obviously

did not make the top ten in growth. As to the great recession of

2007-2009, the entire 28-member EU brethren had to deal with that

contraction.

It’s very

obvious that some member states are gaining more from the union than

others, judging by highly diverse Gross Products. During the 2005-2015

decade, the latest states to become EU members have outperformed most of

the older member states in GDP, substantially. Only Luxembourg, the

United Kingdom and Germany standout as better than Europa (Old Europe)

states. Isn’t GDP a valid test in judging the ultimate value of a

country’s trading partners. We think so.

Assuming administrative

problems are made palatable in future workouts, there is a major

technical subject that will eventually surface—the defense pact with

NATO. This is certain, since UK maintains the biggest military in the

EU. Preventing the loss of the UK’s well-trained military could cause

the EU to negotiate more liberally, with the maverick outsider across

the channel.

Acknowledgments: Images: Theresa May, Harold Wilson, Angela Merkle, David Cameron (Creative Commons license); Pro EU rally/The Guardian (fair doctrine license).

No comments:

Post a Comment