In 1999 a very angry Ron Howard sent this letter to Newsweek after they published an article criticizing the acting skill of a 9 year old Jake Lloyd as Anakin Skywalker in Phantom Menace.

"Vovo" Grandpa Joe Goes Viral

|

| Novena’s centenarian “vovô” Joe Wallach, young-at-heart goals personified. |

He was so inspiring, that there's a couple of merch items in NPR's Spring Pledge Drive collection at the station dedicated to "Grandpa Joe" and a mythical record store called "Joe's Records."

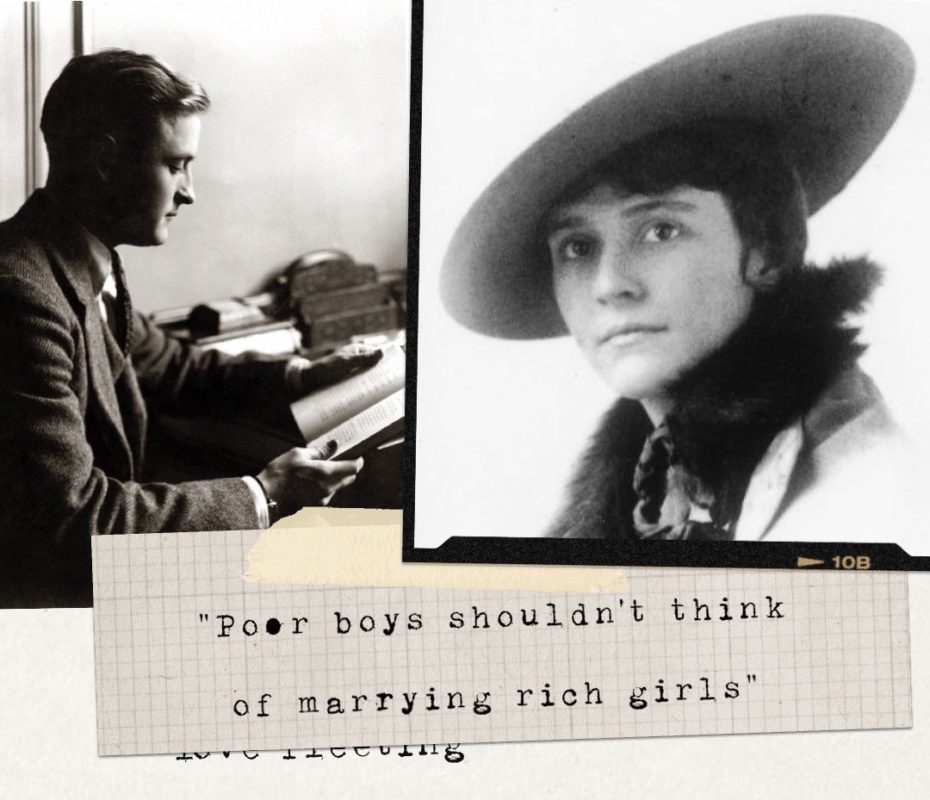

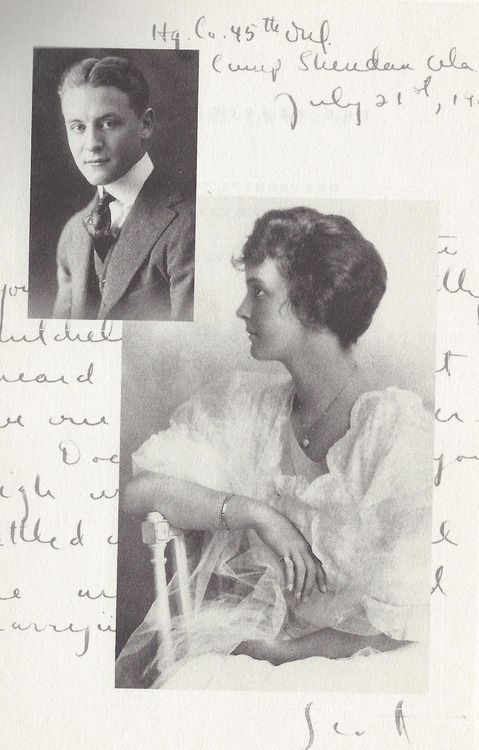

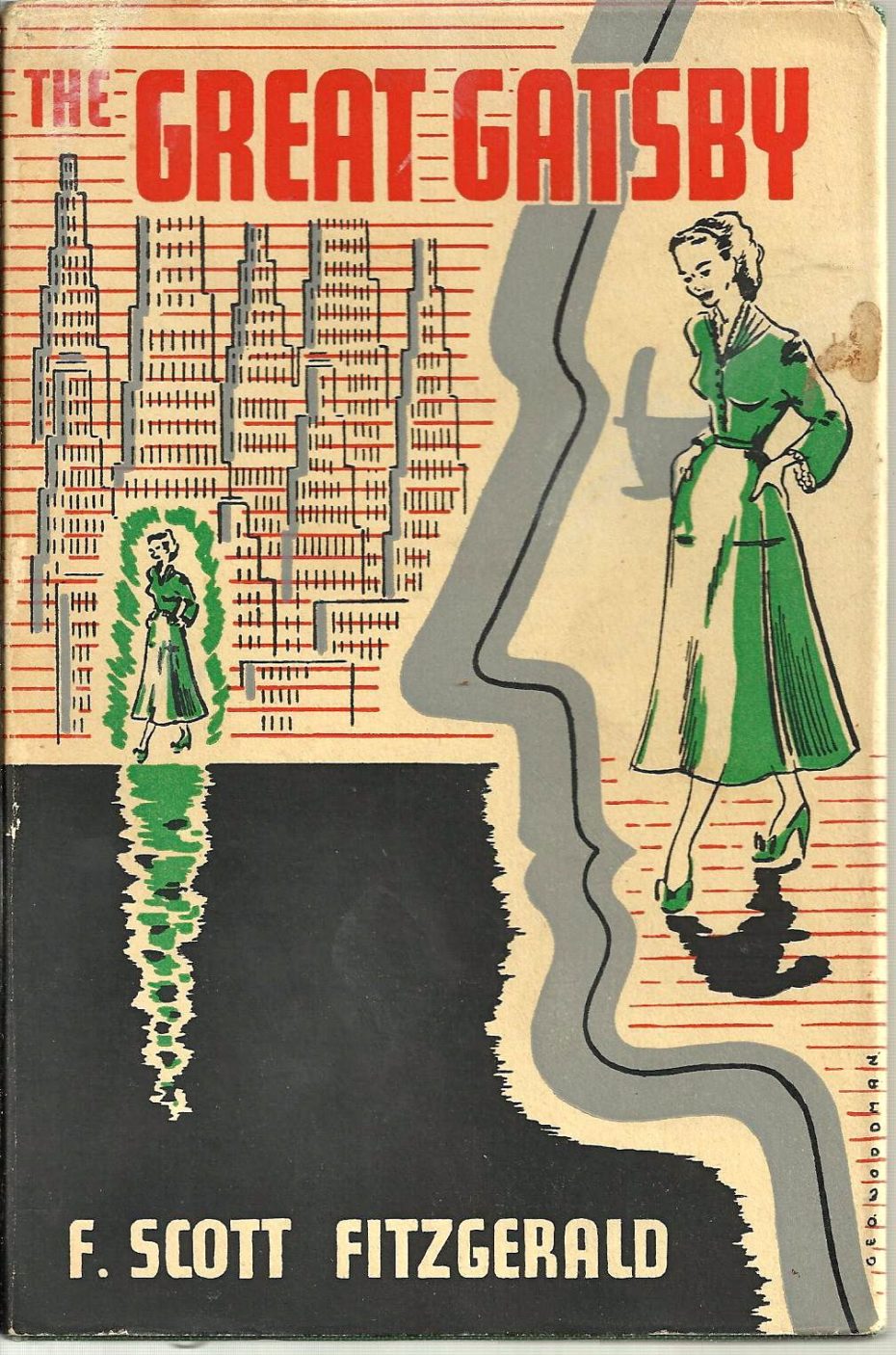

Fitzgerald’s First Love

Like her mother and grandmother before her, Ginevre King was named after Leonardo Da Vinci’s portrait of Ginevra de’ Benci. And she had many parallels with the Italian aristocrat: King also came from immense wealth and would be most remembered for how she was depicted by one of her era’s most famous creatives, in her case the author F. Scott Fitzgerald. King supposedly provided inspiration for Daisy Buchanan in Fitzgerald’s 1925 classic The Great Gatsby. But beyond these surface level details, King’s story becomes much more complicated. In addition to having a star-crossed romance with the American literary giant, she was the author of the text that provided a clear inspiration for The Great Gatsby, raising the question of whether King was simply a literary muse or a victim of Fitzgerald’s plagiarism.

Born in 1898 in Chicago, Ginevre King grew up in immense privilege as the daughter of a socialite and financier. She arrived on the Midwest city’s social scene as one of the “Big Four” debutantes during World War I. As Maureen Corrigan wrote in the 2014 book So We Read On: How The Great Gatsby Came to Be and Why It Endures, King grew up in a “life of tennis, polo ponies, private-school intrigues, and country-club flirtations.” But she also knew the power of her family’s position and wealth; as Coorigan wrote, she had “a highly developed understanding of how social status worked.”

In 1914, Ginevre was sent to the Westover School, an elite finishing school where her classmates included members of the Rockefeller and Bush families. She was expected to pursue a life of “noblesse oblige,” in which her work commitments didn’t extend beyond childrearing and maintaining her family’s social circle. But things took a turn when 16-year-old King met 19-year-old F. Scott Fitzgerald (then a student at Princeton) at a sledding party in Minnesota while visiting her Westover roommate.

They had only known each other for a few months when Ginevre wrote in her diary that she was madly in love with him. The two began an extensive letter correspondence, with King sharing Fitzgerald’s passionate musings with her school friends. Their letters became increasingly romantic, with the two exchanging photographs. King supposedly would sleep with the letters, hoping “that dreams about him would come in the night”.

Fitzgerald visited the King estate outside of Chicago several times, but King’s parents refused to let her attend Princeton’s sophomore prom, an important social event. King’s father supposedly told Fitzgerald that “Poor boys shouldn’t think of marrying rich girls.” Still, Fitzgerald didn’t give up his ill-fated affair, writing a short story in 1916 called “The Perfect Hour” in which he imagines himself finally with King. He sent her “The Perfect Hour,” which she read to one of her other male boyfriends — he at least praised Fitzgerald’s excellent prose. As a response, King composed another short story in which she imagines herself in a loveless marriage to a rich man, still yearning for her ex-lover, Fitzgerald. The two are reunited after Fitzgerald makes his own fortune, hoping to win her back. Sound familiar? She sent the short story to Scott in March of 1916, seven years before the release of The Great Gatsby.

By 1917, the real relationship between King and Fitzgerald had fizzled, and she went on to enter an arranged marriage with William Mitchell, a rich Chicagoan and polo player. Meanwhile, a depressed and heartbroken Fitzgerald enlisted in the Army to fight in World War I. The future American literary giant kept a copy of Ginevre’s short story with him for the rest of his life, though he did have King destroy the letters he sent her.

“Because she’s the one who got away, Ginevra—even more than Zelda—is the love who lodged like an irritant in Fitzgerald’s imagination, producing the literary pearl that is Daisy Buchanan”, notes scholar Maureen Corrigan, who believes that Scott’s works are full of characters inspired by King, including Isabelle Borgé in This Side of Paradise (1920), Judy Jones in Winter Dreams (1922) and Paula Legendre in The Rich Boy (1924).

Sessue Hayakawa

Director Cecil B. DeMille used the Eastern atmosphere to give a proto-noir sheen to the story of a foolish society woman with a cash-flow problem and the rich ivory merchant who loans her money in exchange for her sexual favors.

Women went wild for Hayakawa. When the highly successful film was re-released in 1918, the ivory merchant’s nationality was changed to Burmese to appease protests from the Japanese community in southern California. Hayakawa’s career was crowned by an Oscar nomination for Bridge on the River Kwai in 1957.

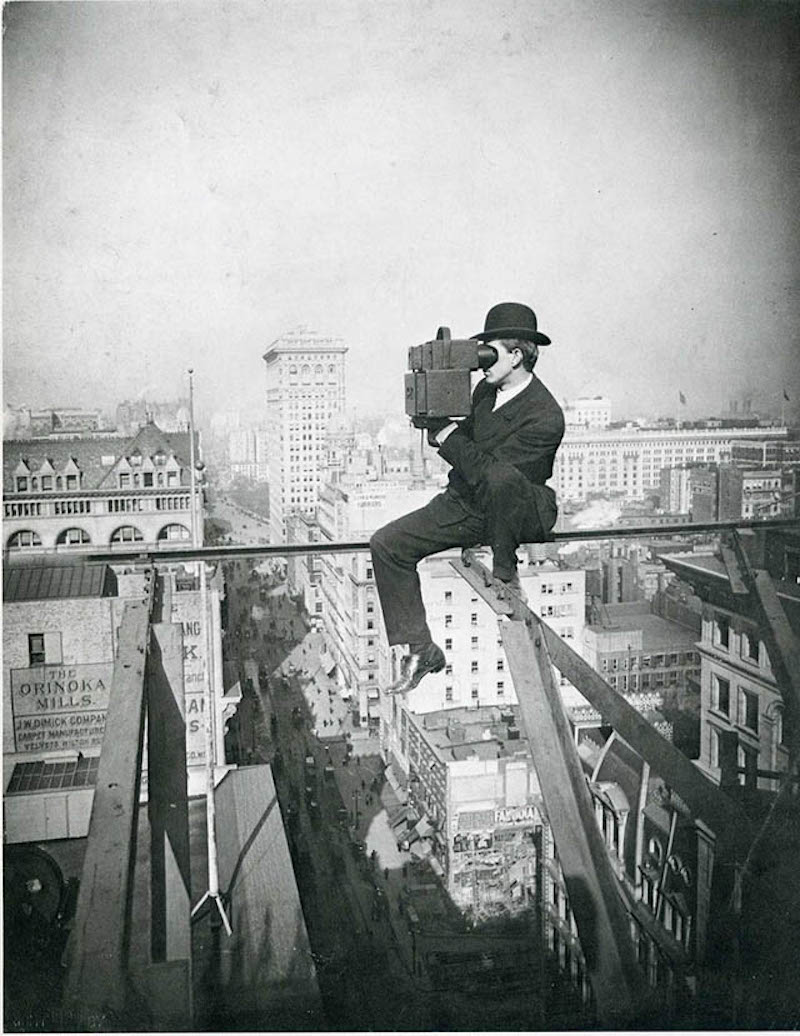

CHARLES C. EBBETS

TEE TIME © BETTMANN ARCHIVES, CORBIS

© BETTMANN ARCHIVES, CORBIS

© BETTMANN ARCHIVES, CORBIS

© BETTMANN ARCHIVES, CORBIS

© BETTMANN ARCHIVES, CORBIS

© CHARLES C. EBBETS

Ebbets, pictured above, was a daredevil himself, and his biography tells of his earlier stints working as a stuntman in Hollywood, as well as an actor in the mid 1920s, playing the role of an African hunter known as “Wally Renny” in several motion pictures. He also had many other jobs including pilot, “wing-walker” (just accept that was a thing), auto racer, wrestler, and hunter. You can see photographs of Ebberts in his many other lives on a website established by his daughter, who has been archiving and restoring his vast collection of pictures.

© CHARLES C. EBBETS

But Charles was always a photographer. He bought his first camera when he was just 8 years-old and charged it to his mother’s account at the drugstore. By the age of 27, he was appointed the Photographic Director for the Rockefeller Center’s development. It was during this appointment, that Ebbets took his iconic “Lunch atop Skyscraper” on the 69th floor of the RCA building in the last several months of construction.

So why did it take so long for him to be credited for it? It has been claimed that multiple photographers collaborated on the shoot, which is likely true because, unless they were self-portraits, we do have several photographs of Charles himself taken that day by at least one other photographer. And who would blame them? The dapper Mr. Ebbets , pictured above and below, was ever so photogenic.

© CHARLES C. EBBETS

The photograph initially appeared in the New York Herald Tribune shortly after it was taken, but it didn’t achieve its iconic status until much later. Back then, photographers weren’t considered artists, they were just the operators behind the machine. They billed their employer for the work. moved on and more often than not, their images were filed away, uncredited in the news archives.

To eventually prove that their father was the artist, the Ebbets family found original invoices billing for his work done at the Rockefeller Centre, copies of the newspaper article found in his personal scrapbook and his original glass negatives that day on the beam adjacent to the 11 workmen. They are now stored in a refrigerated cave in western Pennsylvania, encased in cool limestone bedrock to prevent it from rotting and decaying any further.

via Messy Nessy

1955 letter to Marilyn Monroe from John Steinbeck

Before There Was Emily in Paris, There Was Sally Jay Gorce

Throughout the latter half of the twentieth century and well into the beginning of the next, it’s easy to track our fascination with young women attempting to figure out life – they are witty, tenacious, and often keenly perceptive of the world in which they exist and their place within it. Their names have become household, pop-culture gospel: Holly, Carrie, and now (for better or worse) Emily. But there is one name on that list that often fails to come up: Sally Jay Gorce.

Now, let’s go back for a moment. In November of 1958, Esquire magazine began serialising a novella that told the story of a young woman living in New York. She was a bit of a party girl, and she was looking for a rich man to make all her dreams come true. What those dreams were, exactly, no-one was really sure. Its author, Truman Capote, had originally sent the story to Harper’s Bazaar, who later backed out on the basis that it was just a bit too risque. As well as being serialised in Esquire, the novella was published in full by Random House. It was called Breakfast at Tiffany’s. By 1961, it had been adapted for the screen into what would become one of the all time greats, Audrey Hepburn stepping into the OG little black dress in a performance that would both irk (one person, Capote, who wanted Marilyn Monroe) and bewitch (everyone else, who, as the saying goes, either wanted to be her or be with her.)

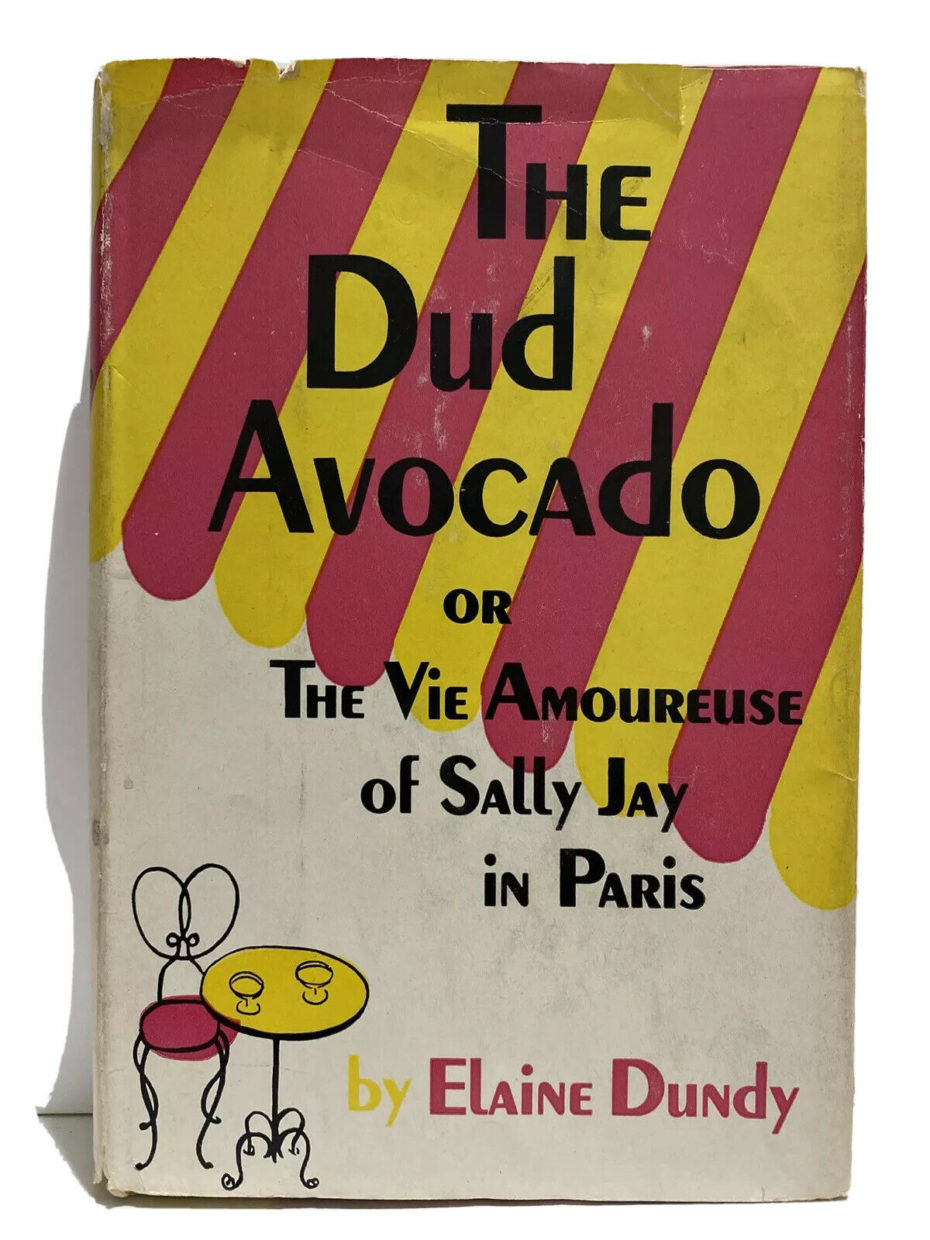

But also in 1958, some nine months before Breakfast at Tiffany’s was published, there was another novel making the rounds, already on its way to becoming a cult favourite. In January of that year, the writer Elaine Dundy – previously an actress in Paris and London, now married to the theatre critic Kenneth Tynan and a new mother – had released her first novel into the world. She called it, rather coyly, The Dud Avocado.

Elaine Dundy based the novel on her own exploits when she lived in Paris for a year before heading to London to act. “All the outrageous things my heroine does, “ Dundy has stated in interviews, “like wearing an evening dress in the middle of the day, are autobiographical. All the sensible things she does are not.” Groucho Marx, who loved the book, sent her a note: “If this was actually your life, I don’t see how the hell you ever got through it.”

Dundy’s method of using her own life as a springboard is similar to that of another woman several decades later, who in November of 1994 began writing a column for the New York Observer detailing the exploits of her and friends as young women making a life – “Well, but living you know…” – in the Big Apple. She called the column Sex and the City.

In Memoriam

The Flying Housewife

Geraldine “Jerrie” Mock became the first woman in history to fly solo around the world on this day in 1964. Nicknamed "the flying housewife" by the press, Mock circumnavigated the Earth flying a Cessna 180 single-engine monoplane; 27 years after Amelia Earhart's famous and ill-fated attempt. Despite her incredible record-making feat, Mock's name is largely unknown today.

In an interview before her death, the Ohio native said, “I did not conform to what girls did. What the girls did was boring.” At age 7, after taking a short airplane ride at a nearby airport, Mock declared she wanted to be a pilot. Several years later, following Amelia Earhart’s adventures on the radio, she dreamed of making similar flights. “I wanted to see the world,” she remembered. “I wanted to see the oceans and the jungles and the deserts and the people.”

She was the only woman in the aeronautical engineering class at Ohio State University, where the male students left her alone after she got the only perfect score on a difficult chemistry exam. But in 1945, women rarely pursued aeronautics careers, and at the age of 20, she dropped out of college to marry Russell Mock. Soon, Mock was busy with her role as wife and mother of three, but she still dreamed of flying. Once her oldest children were in school, she started taking flying lessons and earned her pilot's license. When Mock tired of her ordinary life at home, she complained to her husband about being bored. “Maybe you should get in your plane and just fly around the world,” he joked, but Mock decided he was right.

She spent a year preparing for a round-the-world flight, helped by fellow pilots and navigators who thought she was crazy to want to undertake such a dangerous endeavor. At the age of 38, she began her flight on March 19, 1964 -- two days after another woman, Joan Merriam Smith, also departed on a solo round-the-world attempt.

Mock never wanted to capitalize on her fame, preferring solitude and quiet: “The kind of person who can sit in an airplane alone is not the type of person who likes to be continually with other people,” she explained. After 1969, finances prevented her from ever flying an airplane again. And while she recognized the significance of her flight, achieving the record was not as important as the joy she took in flying. In interviews on her various stops during the flight, she demurely said, “I just wanted to have a little fun in my airplane.” Jerrie Mock passed away in 2014 at the age of 88.